Little mouse on the prairie

Sam Speck's undegraduate research shows how changes in prairie mice communities affect wider grassland ecosystems

et Sam Speck tell you about the simple white-footed mouse and what it means for the future of Kansas ecology.

Let him explain how these small creatures signal major shifts in native prairie environments and are themselves essential players as ecosystems change. Let him walk you through the implications of those changes, including an increase in ticks and related potential for disease in humans.

Speck, senior in conservation biology in Kansas State University’s College of Arts and Sciences, leads undergraduate research that tracks long-term changes in the types of mice found scurrying around the Konza Prairie Biological Station.

Through his work at the Long-Term Ecological Research, or LTER, site, Speck is uncovering new insights into how woody encroachment — the takeover of native prairie grasslands by shrubs and trees — affects wildlife populations, with implications for human health.

During his first semester at K-State, Speck remembers being enthralled by the research opportunities that Andrew Hope, associate professor of biology, described in his mammalogy class. At the end of the semester, Speck emailed Hope to see how he could get involved. He soon found himself curating specimens in the Kansas State Biorepository, a museum that preserves mammals and their parasites for research and education.

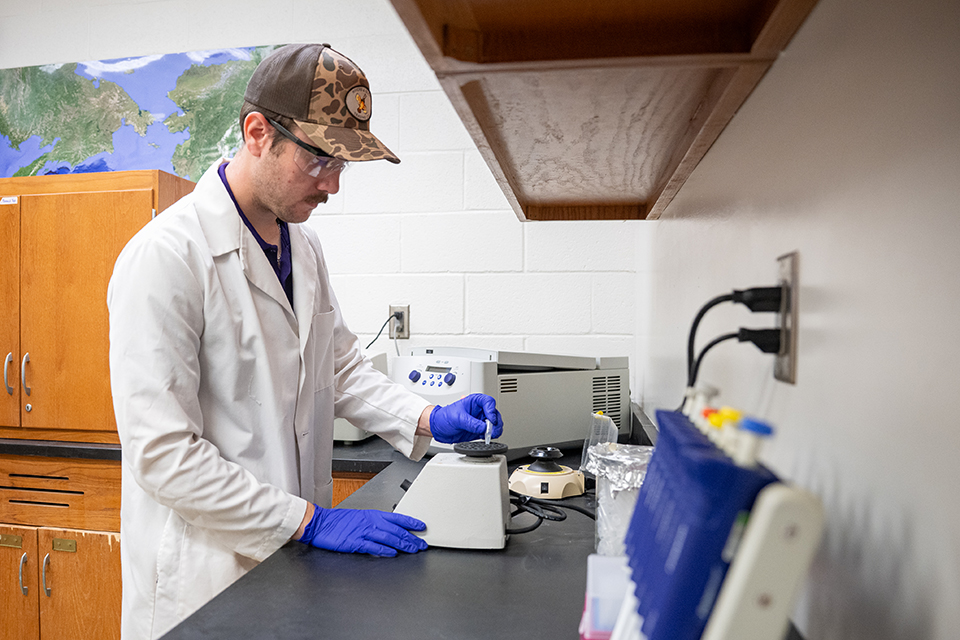

That first job also involved DNA extractions in the lab, and soon after, Hope helped Speck transition into fieldwork at Konza.

Sam Speck, junior in conservation biology, is leading undergraduate research on trends in prairie mice community genetics that show broader changes in the grassland ecology.

Woody encroachment and prairie mice patterns

As Speck became more involved, he joined a project analyzing decades of LTER data on mice trapped at Konza.

“In the field, we were starting to see way more of the white-footed mouse, and that wasn’t the case even 10 years ago, when the deer mouse was still more abundant,” Speck said.

That shift matters. The white-footed mouse thrives in wooded or shrubby areas, while the deer mouse has traditionally been more typical in prairie grassland environments.

Speck’s next step was to compare these changing mouse populations with data showing increasing densities of ticks. He then worked with assistant professor of biology Zak Ratajczak to combine those observations with plant datasets. Together, they traced how shifts in vegetation influence small mammals and parasites.

They found that in areas of the Konza Prairie that had not been burned frequently, shrubs and trees were moving in, and with them came a substantial transition from deer mice to white-footed mice.

“K-State is uniquely situated to provide hands-on research experiences because it prioritizes faculty and teachers who are invested in connecting students to these career-building opportunities.”

“With that comes increases in zoonotic disease risks for humans,” Speck said. “The white-footed mouse can carry many kinds of diseases that can then be transmitted to humans. As densities of both mice and ticks become more abundant in woodland areas, so does the potential for disease.”

These mice are closely associated with ticks that carry Lyme disease, and Kansas has begun to see more reported cases of Lyme each year. The data suggest that could be connected to the increases in white-footed mice across the state.

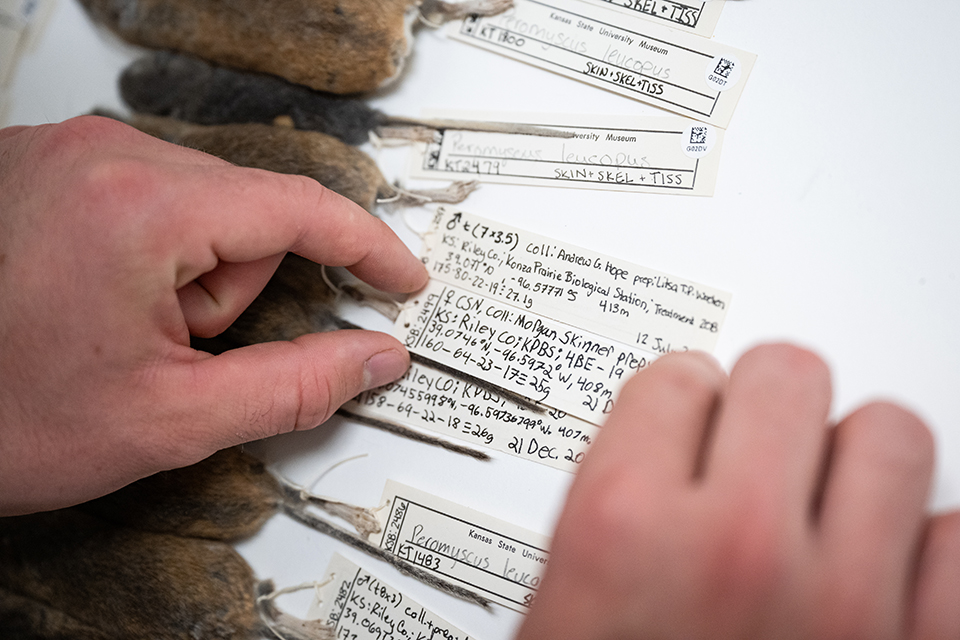

The samples preserved in the Biorepository provide a long-term record of biodiversity and habitat change across Kansas and the Great Plains. By comparing Konza data to historical specimens in natural history museums, researchers have observed similar mouse population shifts across the state, especially in areas where prairie burns have become less frequent.

Speck’s findings are under consideration for publication in the journal BioScience.

“We take mice for granted, mainly because they’re so abundant everywhere,” Speck said. “But because of that, they’re actually an excellent way to study the underlying ecological mechanisms in an environment. It’s kind of cool that this one little mouse can tell you so much about what’s going on in the broader scheme of nature.”

Through his undergraduate research, Sam Speck is analyzing historical mice samples from around Kansas kept at the Kansas State Biorepository, a mammal collection with more than 2,500 specimens in the Division of Biology.

Making a difference through parasite research

Hope said Speck’s research is important because it bridges long-term ecological data and museum collections with real-world human health implications.

“This is pretty new and opens up opportunities for more student research in the future,” Hope said. “Sam’s keen interest in studying the relationships between parasites and their mammal hosts is a great starting point for a successful transdisciplinary career.”

Through his experiences, Speck said he has found a passion for parasitology, a field where he believes he can make a meaningful difference.

“I want to do research that impacts people in a way that matters,” Speck said. “Parasitology is a field where I think I could do that. Here in the U.S., we don’t feel the effects of parasites as much, but around the world, millions of people suffer from them. I’d love to work in that field and maybe even one day come back to K-State as a professor.”

That ambition will take hard work, but Speck said he feels supported and prepared.

“K-State is uniquely situated to provide hands-on research experiences because it prioritizes faculty who are invested in connecting students to career-building opportunities,” he said. “I’ve had so many of those here, and it’s helped me build a resume that’s going to set me apart as I pursue my dream.”![]()

◊◊◊

Seek magazine

Seek is Kansas State University’s flagship research magazine and invites readers to “See” “K”-State’s research, scholarly and creative activities, and discoveries.