How a K-State grad student’s rooftop research could change the way cities stay cool

Graduate landscape architect Muhaiminul Islam bolsters green roof resilience

s cities get hotter and drier and wildlife becomes sparser in urban areas, there's a solution as old as civilization itself.

Green roofs, appearing as far back as the Neolithic period, are thin layers of soil and vegetation installed on residential or commercial roofs. These early types of roofs served practical purposes such as insulating homes, managing rainwater, and blending shelters into their surroundings.

Though the concept has endured, builders and landscape architects have refined designs — including through research atop some of Kansas State University's iconic limestone buildings.

Under the tutelage of Lee Skabelund, associate professor in landscape architecture, graduate research assistant Muhaiminul Islam is advancing sustainable solutions in archiecture by optimizing the irrigation system of K-State's green roofs.

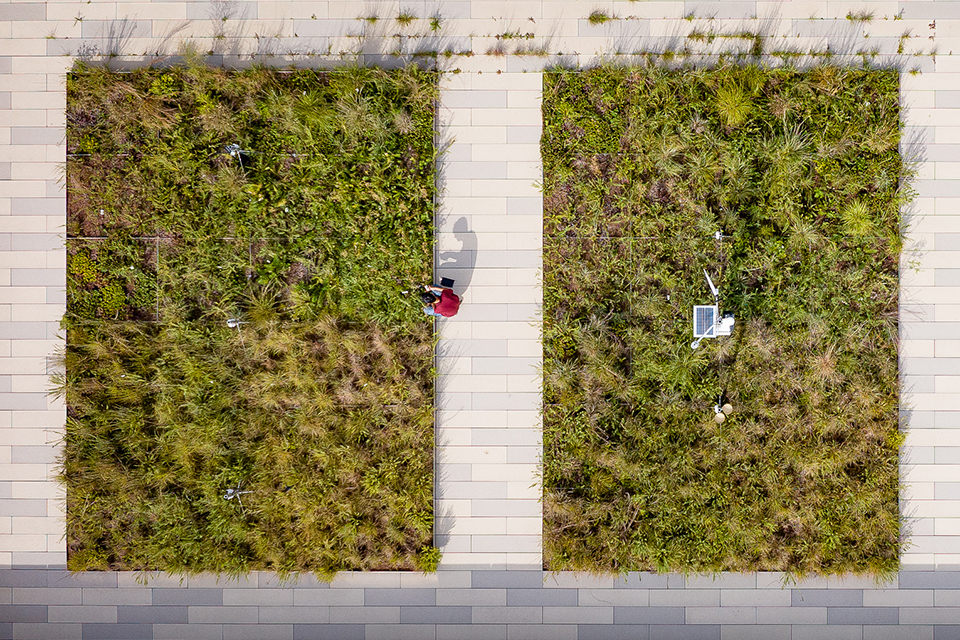

On an experimental green roof above K-State’s Regnier Hall, Muhaiminul Islam is using advanced soil moisture sensors to test different types of soils and irrigation level patterns, showing the potential for green roofs as a sustainable solution even in arid regions and urban communities.

Modern green roofs typically feature a structural membrane, a drainage layer, lightweight soil and substrate mix, and plant life.

On experimental green roofs atop Regnier Hall, Islam and Skabelund monitor separate green roof beds with varying depths: approximately four-inch extensive beds, six-inch semi-intensive beds and eight-inch intensive beds. Two substrate varieties are used: Rooflite, lighter with more organic matter; and Kansas Build-X, sandier, slightly heavier and denser.

“One of the main goals of my research is trying to explore if the substrate type makes significant difference in plant cover under different irrigation frequency — which plants perform better in under minimal irrigation,” said Islam, Jarvis Graduate Research Fellow for K-State’s Green Roofs Lab. “This is important because it can provide guidance to the green roof industry, especially in regions with less rain and more drought periods.”

A TEROS 12 advanced soil moisture sensor captures the volumetric water level and temperature of the soil, and a K-State Agronomy weather station records precipitation, air temperature, relative humidity, and wind velocity data.

To control irrigation frequency, the researchers use a long hose to water plots by distributing stormwater collected from the rooftop and stored in an 800-gallon metal cistern. During dry spells, the researchers can also tap into potable water supply points to maintain consistent watering pressure and amounts, informed by data from the sensors and a weather station.

“For my experiment, half of the plots get more irrigation and half get less irrigation,” Islam said. “When the soil moisture level is below 8% and chances of rain in the next 24 hours are less than 50%, we irrigate half of the plots that get more irrigation. When the readings go below 8% next time, we irrigate all plots. This is how half the plots get more irrigation and half receive less.”

Islam takes overhead photographs and then monitors the plant dynamics through an app called Canopeo, recommended by Andres Patrignani, assistant professor of agronomy and member of Islam’s committee. This app allows agricultural producers to measure the canopy cover and growth of crops and allows the research team to see how plant canopy cover is impacted by irrigation frequency and substrate type and depth.

One finding came in 2023, when the researchers stopped irrigating some of the beds. While some of the plants began to wither, not all of them did — showing green roofs may be more feasible in water-poor environments than previously thought.

“Over the course of one year, the part we did not irrigate got very dry,” Islam said. “But there are some green roofs we don’t irrigate at all, and many plants survive. This indicates that low maintenance green roofs are possible, and we can save water.”

Improving research, communities and the climate

One of Islam’s proudest moments may benefit future researchers.

While the agriculture community has created standard calibrations for the TEROS 12 sensors, green roof soils differ. Through his research, Islam is helping define a custom calibration for these sensors when used in green roof monitoring.

“After several attempts in Dr. Patrignani’s lab, it finally worked, and it was a very happy moment for me,” he said. “I plan to publish an article about this new calibration equation which may help other researchers.”

Beyond green roofs, Islam’s academic projects include conceptual redesigns for parks and sites in Kansas City, Missouri, and Albany, New York, and K-State’s Edwards Hall, focusing on water efficiency, habitat diversity and community spaces.

Each of these three projects has earned Islam a total of six honor and merit awards from the Central States and Prairie Gateway chapters of the American Society of Landscape Architects.

“Green roofs help absorb the heat, attract local pollinators and hold rainwater to help the runoff process. It serves those communities, not only for humans but also for the planet.” ”

Over the summer, Islam worked as a landscape architecture intern with K-State’s Technical Assistance to Brownfields program, which equips communities with the expertise and guidance needed to revitalize land that may be contaminated with hazardous substances. Islam supported multiple site and urban design projects in Kansas, Montana and Oklahoma.

With one community facing a decline in services and recreational opportunities and another dealing with a lack of housing amid population growth, Islam said the internship taught him to address unique challenges with practical, lasting solutions.

“In real life, each project comes with very different challenges,” Islam said. “Without this internship experience, I would not have learned how understanding the needs of the community is very important for us as designers.

“If we understand the root of the problem, our design solutions can help to create a longer-lasting impact.”

Regardless of location, Islam said one of his primary concerns is addressing our planet’s changing climate. He explained that researching green roof technology is particularly significant due to its potential impact on urban communities.

Due to the lack of vegetation and increased presence of man-made materials, larger cities face unique challenges such as flash flooding, decreased biodiversity, lack of public spaces and temperatures up to 7 degrees Fahrenheit higher than the surrounding rural areas, he said.

“Green roofs help absorb the heat, attract local pollinators and hold rainwater to help the runoff process,” Islam said. “Aesthetically beautiful roofs can become public spaces and improve health and wellbeing. It serves those communities, not only for humans but also for the planet.” ![]()

◊◊◊

Seek magazine

Seek is Kansas State University’s flagship research magazine and invites readers to “See” “K”-State’s research, scholarly and creative activities, and discoveries.