'A silent symphony’

How Juergen Richt conducts a team tackling the world’s emerging animal diseases

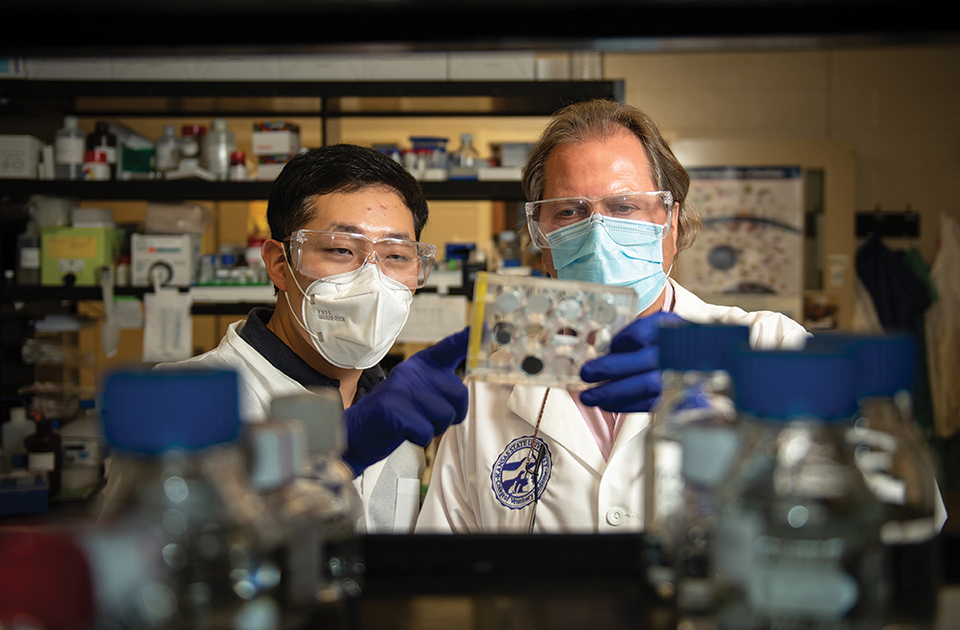

Over the course of his career, Juergen Richt has mentored and developed dozens of members of the next generation of animal disease experts.

What millions of years of incremental biological evolution developed takes only the better part of an afternoon for Juergen A. Richt and his team of animal disease scientists to deconstruct.

In the pioneering veterinary researcher's laboratory, Richt's cadre of experts and technicians in specialties like virology, immunology, molecular biology, animal husbandry and pathology make short order of some of the world's most mysterious and perplexing animal diseases.

Livers are dissected. Lungs are flushed out. Blood and tissue samples are studied. The team moves in the coordinated synchronization of a Bach-like orchestral symphony, with the German-born scientist conducting with calculating precision.

"In high-containment labs, we don't talk much, if at all," said Richt, a university distinguished professor in diagnostic medicine and pathobiology. "Under the muffling of all of our personal protective equipment, this has to be a well-oiled machine where people know their roles and their work is automatic to them. It's like a silent symphony, and it's the most beautiful thing in the world to me."

Over the last two decades, Richt has built his laboratory at Kansas State University into a research machine that tackles emerging diseases hiding in rainforests, jungles and deserts in some of the world's most remote pockets, before they become global threats.

The team's research output has earned Richt numerous accolades. In addition to receiving K-State's highest honor for professors, Richt is also a Kansas Regents distinguished professor and a Kansas Bioscience Authority eminent scholar.

This past year, he was elected to the National Academy of Medicine — one of the highest honors in the fields of health and medicine that recognizes individuals who have demonstrated outstanding professional achievement and commitment to service — and this month, he was elected to the American Academy of Microbiology.

But more than any single preventive measure, cure or vaccine, the achievement Richt is most proud of is the development of students and researchers into veterinary researchers and pioneers.

"The people who come from my lab learn that nothing comes easy without hard work ," Richt said. "It's the same at any level and in any industry. That's what we teach and develop here. It's hard work and discipline, with a mix of intelligence. Success doesn't fall from the sky like manna. You have to put in serious effort to be successful – there are no shortcuts."

Becoming an animal disease researcher

Richt knows the value of good mentorship and encouragement because he had it from the very start. Richt was raised on a farm in south Germany, raising everything from dairy cattle to pigs to chicken.

"I was always exposed to this kind of work, but I ended up becoming a veterinarian because of my piano player hands," Richt said with a smile. "The local veterinarian always told me, 'You have the right hands to pull piglets out of sows.'"

The local veterinarian was right, and as Richt followed his interest in veterinary medicine and animals, he was fascinated by the study of veterinary medicine and how naturally the subject came to him.

"I think it was easy for me because I liked it, and I liked the variety of work available in the field," he said. "There were so many options, from research to clinical work to food safety to pathology — you name it, the whole nine yards were available."

Richt earned his Doctor of Veterinary Medicine from the University of München in 1985 and his Ph.D. in virology and immunology from the University of Giessen in 1988 — both in Germany. At the latter, Richt researched under Rudolph Rott, a world-renowned pioneer in the study of influenza viruses, particularly swine and avian influenzas. Rott founded Giessen's Institute of Virology, which was the first of its kind in Germany.

Richt then completed his veterinary residency at The Johns Hopkins University under Opendra "Bill" Narayan, an eminent expert in developing animal models of HIV.

Narayan — a Guyanese son of a sharecropper who came to North America with only $100 — was the one who taught him "the American way," Richt said.

"Bill was the one who taught me to write well, using proper English," Richt said. "I learned the American way and how to write beautiful papers and present well from him. These were things I couldn't learn in Germany, where there was just a different approach to this kind of work."

Making K-State a leader in emerging zoonotic diseases

After his residency and a few years in Germany, Richt was hired as a veterinary medical officer for the U.S. Department of Agriculture in Ames, Iowa.

It was in this role that he really began to sink his teeth into translational, mission-oriented research, scientific innovation that has a direct connection to applications in the field to improve human and animal health.

"Through translational research, I could produce tools and gadgets for the farmer and for the field," Richt said. "I really enjoyed getting to work with animals like pigs, sheep, cattle, and wildlife, especially cervids, studying diseases like swine flu or prion diseases of cattle, sheep, deer, elk or reindeer — you name it."

When K-State was building Pat Roberts Hall on the north end of campus to house the Biosecurity Research Institute, university officials knew that, for the lab to be successful, it had to have the right people behind it.

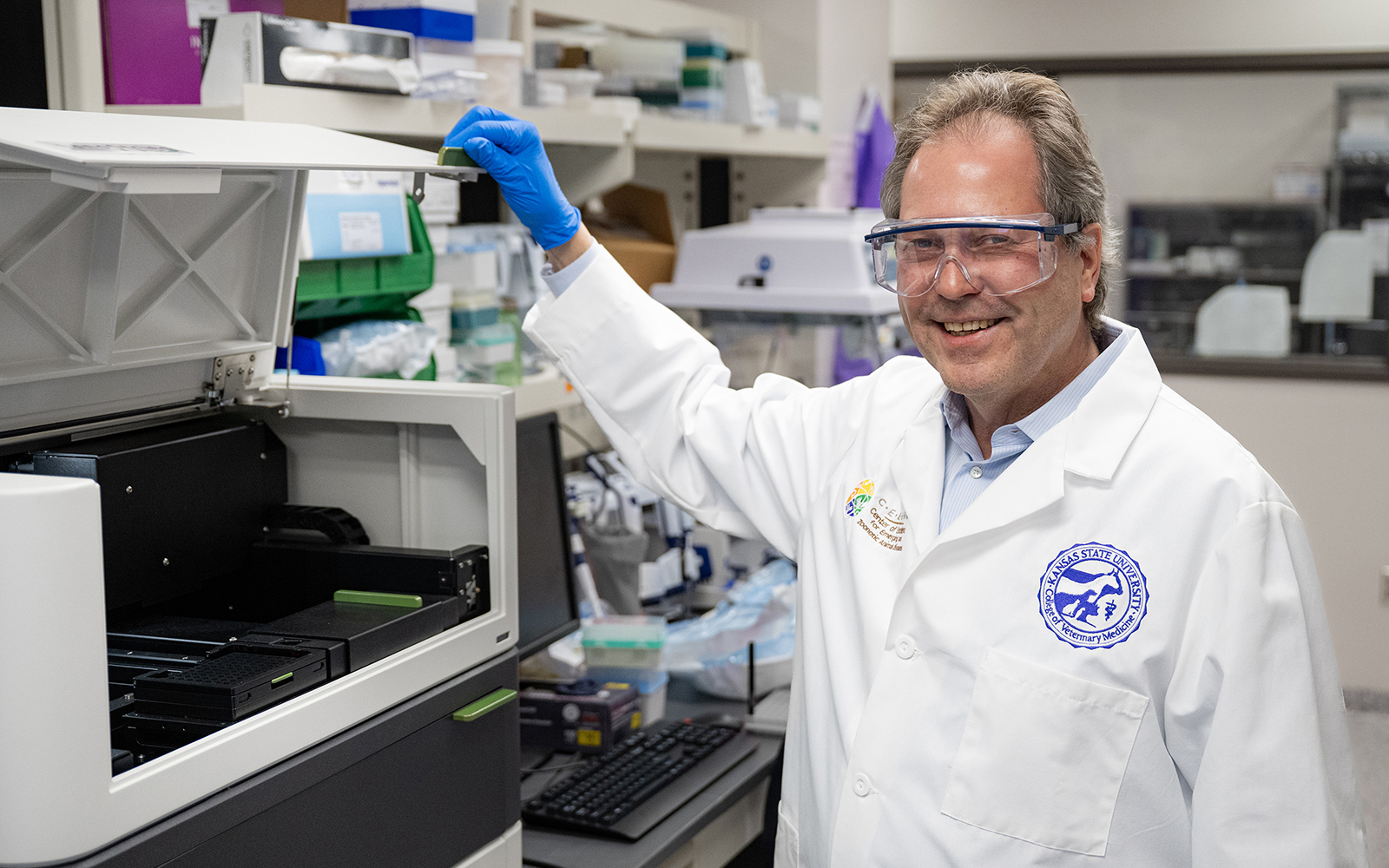

They recruited Richt to K-State, and in 2010, he became director of the university's Center of Excellence for Emerging and Zoonotic Animal Diseases, or CEEZAD — a U.S. Department of Homeland Security Center of Excellence. Later in 2020, he was named director of the similarly focused Center on Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, or CEZID, through the National Institutes of Health.

Housed at K-State, both centers have led multi-institutional efforts to develop vaccines, detection technology, prevention and control measures, and education and training to investigate the world's newest and most consequential diseases of animal origin.

Over the years, that work has included research on animal viruses like H5N1, which causes Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza among birds and various mammals including cattle, African Swine Fever virus, which causes a lethal disease in domestic pigs and wild suids with major global animal health and economic losses, and prion diseases like bovine spongiform encephalopathy, more commonly known as mad cow disease.

Richt's work, however, often takes him across the world to investigate the needle-in-a-haystack-like diseases that suddenly occur, like SARS CoV-2, or other globally emerging diseases like Japanese encephalitis and Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever, or CCHF.

CCHF — spread by ticks and endemic across parts of Africa, the Middle East and Asia — has recently spread, with reports of the disease being present in Spain.

Even though CCHF is not yet endemic in North America, Richt underscored his lab's work in understanding and mitigating diseases like it before they become cause for global concern.

"When we look at diseases, we're not looking at them from a K-State standpoint," Richt said. "We're looking at diseases from a global perspective and trying to understand how these diseases move in their natural environment and might spread around the world and affect livestock and humans."

Building people

There are three types of infrastructure at play when building research laboratories: brick-and-mortar infrastructure, financial infrastructure and personnel/intellectual infrastructure.

With his office and primary lab space in the College of Veterinary Medicine in the long shadow of Bill Snyder Family Stadium on K-State's north campus, Richt often compares the work of building a research lab to the work the legendary football coach Bill Snyder did across the street.

"When K-State built the BRI, the idea was that if we build it, the people will come," Richt said. "But that still took a lot of work — finding people with the right experience or who were willing to learn to work in a BSL-3 biocontainment laboratory with livestock. We had to build that capacity from scratch, and after that, we had to identify research areas that would be critical for agriculture, public health and the nation.

"We did that, and when we found our niche, we became an entity that is recognized nationally and internationally," he continued. "We did what made sense for Kansas State. Bill Snyder did it for football, and we did it for zoonotic diseases."

Over the past 15 years, Richt’s research enterprise has secured nearly $80 million in competitive funding — support that spans federal agencies, industry partners and international funding entities.

“When we're pushing the envelope the way we do with zoonotic diseases, we're often the first to learn about the intricacies of these diseases. We break barriers. We're the first in the world to discover things. That still excites me, this many years later.”

JUERGEN RICHT

It's an impressive amount for any researcher, but for Karinne Cortes, it's a reflection of the environment Richt created where intellectual infrastructure thrives.

"You don't hear of very many professors, even globally, who can get that amount of grant and award funding," said Cortes, who has been by Richt's side as lab compliance manager since he came to K-State. "He's a very motivated, dedicated researcher, but more than anything, he makes it a fun, encouraging work environment, and it's his passion that moves this team forward, always looking for our next challenge."

Across K-State and around the world, Richt has built a reputation for developing talent — attracting top graduate and doctoral students from around the world while also investing deeply in students already on campus.

Chester McDowell had been finishing a master's in biochemistry in 2012 when his then-research mentor referred him to Richt to get more experience in a "wet lab," a lab that works with actual materials and diseases.

Richt brought McDowell on as a volunteer and then mentored him as McDowell worked up to a research assistant position. When McDowell approached Richt again for advice on pursuing a Doctor of Veterinary Medicine, Richt pushed and supported McDowell to pursue those dreams.

Through a USDA program to train scientists for roles at the National Bio and Agro-Defense Facility, McDowell ultimately earned both his DVM and a Ph.D. in diagnostic medicine and pathobiology.

"Dr. Richt is an inspiring scientist and a great person to work with and learn from," said McDowell, now a veterinary medical officer at NBAF. "He sets high standards for his staff and students, but he prepares us well to reach them and to solve the challenges we face as professionals once we graduate from his lab."

For Richt, research success has never been measured only in publications or funding totals.

Like a maestro whose performance is defined by the musicians playing in synchronized symphony, Richt understands that his true legacy lies in the careers he has helped shape.

“People who have come through my lab have gone on to successful careers in research, industry and government,” Richt said. “It’s an honor and a privilege to know that even when I travel to other continents, I’m rarely more than a country away from someone I’ve helped in their career.

“That’s the beauty of my job — to get to see people grow and reach further success than I could reach alone.”

###

Related Stories

Biomanufacturing initiative links education, industry and workforce needs

Kansas State University is continuing the Multidisciplinary Hiring Initiative in Biomanufacturing with four new faculty hires...

Strengthening global biosecurity

James Stack, university distinguished professor in the College of Agriculture, has been appointed to an endowed professorship...

People with purpose: Laura Miller

With a strong commitment to advancing agile approaches for preventing infectious diseases in dogs and horses, Laura Miller...