People with purpose: Matthew Kirk

Meet the University Outstanding Scholar helping Kansas students and rural households learn about groundwater quality

A University Outstanding Scholar and fellow of the Geological Society of America, Matthew Kirk has taught a wide range of classes and taken on several projects in groundwater-surface water interactions across the region. Learn how Matthew Kirk is integrating engagement into his teaching and research focused on improving the quality of Kansas water.

s a K-State University Outstanding Scholar and fellow of the Geological Society of America, Matthew Kirk has taught a wide range of classes and taken on several projects in groundwater-surface water interactions across the Kansas region.

Throughout his life and academic journey, Kirk has found that his purpose is water research in areas that impact daily life and sharing this passion with students.

Read on to learn, in his own words, how Kirk, a professor of geology in the College of Arts and Sciences, is integrating teaching and research focused on groundwater into Kansas communities.

Q: What has been the most impactful day at K-State for you and why?

Kirk: One of the more impactful days I’ve had here at K-State was July 12, 2022. That was when I found out that the National Science Foundation funded our proposal to create a recruiting network with community colleges and use groundwater quality monitoring as an undergraduate research component.

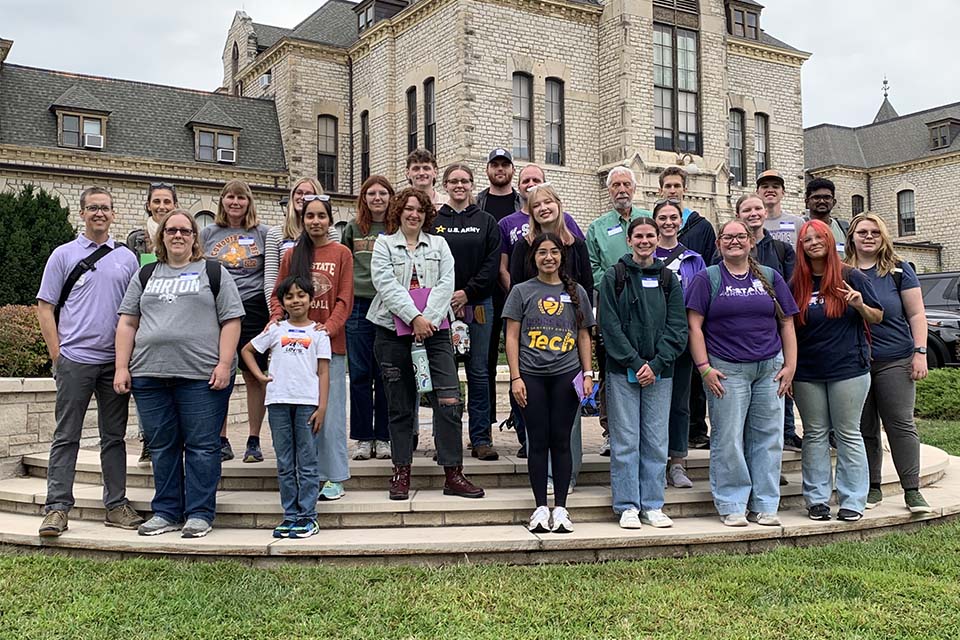

The project has been impactful in terms of opportunities for students, with 58 students participating so far and using the experience to further their goals. It has also helped about 220 households in rural Kansas learn about their water.

Through the program, Matthew Kirk has led teams of students from K-State and community colleges in Barton County and Dodge City to sample water from domestic wells and analyze the water chemistry to measure concentrations of specific contaminants — often nitrate from fertilizer use in nearby crop fields — and overall contamination levels.

Working through this project has also helped me better understand what kinds of research can be impactful. It does not have to be published in the most prestigious journals or come from the largest grants.

It can simply be work that intersects daily life, like research that helps Kansans better understand their water quality.

Q: How did you decide to go into higher education?

Kirk: I was working as a postdoc at Sandia National Laboratories and, although my experience there was truly fantastic in many ways, I had little freedom in choosing my research topics and few opportunities to teach.

As a professor, however, I get both. I get to follow my interests in water research and share that passion with students each semester.

Q: What's the coolest thing in your office and what’s the story behind it?

Q: Kirk: I have an old culture of sulfate-reducing bacteria from 2007, when I was a doctoral student.

I found it in a box of old lab supplies and realized that the precipitate that had long ago formed in the culture had started to develop crystal faces as it transforms to pyrite.

The crystals sparkle when you swirl the water in the culture, providing an eye-catching conversation piece for talking about the interplay of earth and life sciences.

Q: What's your favorite spot at K-State?

Kirk: I really love the Great Room in Hale Library. It is a peaceful and uplifting space.

I also love the murals there and what they bring in terms of history.

Q: What is one thing you want people to know about you?

Kirk: I didn’t actually want to go to college.

I was a first-generation college student who did not feel like I fit in on a college campus, but I stuck with it and eventually developed a love of learning.

The experience helps me remember that we need to be patient and supportive with our students as they find their path and grow.

In one of his geochemistry courses, Matthew Kirk takes students outdoors for hands-on learning by collecting water samples from Campus Creek.

Q: What is your teaching style and what's at the heart of it?

Kirk: If you want to deliver a message, keep it simple.

That idea essentially lies at the heart of my teaching style. By focusing my course content, I avoid diluting key information and my students have time to practice key concepts together before we move on to the next topic.

On the other hand, if we flood students with too much information, they will turn to rote memorization to pass the class and the lessons learned won’t be retained in the long term.

Q: What's your favorite part about working with students?

Kirk: As a professor, I get to talk about stuff that I think is really cool and when my nerdiness rubs off on students, it is just the best.

Q: What professional accomplishment are you most proud of?

Kirk: I got to be a part of the team that created the K-State Environmental Science Program.

The program provides an interdisciplinary pathway for students who are interested in meeting environmental challenges in their careers and making the world a better place.

Q: How do you tailor your teaching to prepare students for their careers?

Kirk: I create opportunities for students to develop practical skills they will need on the job. For my aqueous geochemistry course, for example, we go out and collect water samples right here on campus, using the same approaches used in the environmental industry.

I make sure they know how to use spreadsheets for calculations and data management, and I also make an effort to incorporate real-world datasets.

Q: What might somebody experience in your class that they won't find anywhere else?

Kirk: There will be quite a few references to movies from the 1980s and 90s.

I also almost never use slides but instead use the chalk board for my lecturing. It helps pace the conversation, keeps everyone active and lets students know what to write.

Also, writing can improve retention.

Q: What do you feel is your most significant contribution to research at K-State?

Kirk: I think my most significant contribution to research at K-State is probably the work we did to examine geochemical controls on interactions among anaerobic microorganisms in aquifers. That research was not focused on a place but rather it was focused on identifying relationships that could exist in any anaerobic setting.

As such, the work has broad applicability. Findings can be used to interpret what microorganisms are doing in an environment based on geochemical data. They can also be used to manage microbial reactions for beneficial outcomes such as groundwater bioremediation.

“As a professor, I get to talk about stuff that I think is really cool and when my nerdiness rubs off on students, it is just the best.”

I became interested in this topic when I was working on geological carbon storage as a postdoc. When you inject massive amounts of carbon dioxide into the subsurface, you change conditions considerably.

In turn, how subsurface microorganisms respond to those changes would likely affect the fate of the carbon dioxide, but we were not sure how. I started working on that question as a postdoc and continued working in that area during my first decade at K-State.

Q: What is your long-term goal for your research and where are you in that process now?

Kirk: One of my long-term goals is to integrate teaching and research focused on groundwater. Our co-curricular service-learning project, Kansas Groundwater Geopaths Project, represents solid progress on this goal.

However, next year we expect to take it a step further and create a Vertically Integrated Program, or VIP, defined by a series of formal course offerings.

Matthew Kirk at an outreach event with the Kickapoo Tribe in Kansas in 2018.

Susan Rensing, the associate director of scholar development and undergraduate research, is the driving force for development of VIP offerings here at K-State and the person who presented this opportunity to me and Helene Avocat, my K-State Geopaths collaborator and a teaching assistant professor in geography and geospatial sciences.

We think this project will generate important data on groundwater quality around the state, data that we intend to share broadly through a newly developed Kansas Geological Survey water quality database.

The project will also provide students with hands-on applied learning focused on groundwater, which is an area of strong workforce demand.

Q: What is your favorite way to serve your profession/community and why?

Kirk: My preferred way to serve my profession is through geoscience recruiting.

Geoscientists help protect communities exposed to natural hazards like earthquakes, volcanoes and floods. Geoscientists identify and help manage natural resources including critical minerals, water and energy resources. Geoscientists help us learn how the climate works and seek answers to some of the biggest questions when they look deep into Earth’s history and that of other planets. We do cool stuff.

Nonetheless, course enrollment and the numbers of majors in geoscience have significantly decreased over the past decade in geoscience departments worldwide.

There will be a shortage of geoscientists needed to fill critical roles unless we can improve recruiting, and I want to help.

Since beginning the Kansas Groundwater Geopaths project, Matthew Kirk has provided learning opportunities for nearly 60 students and helped more than 200 rural Kansas households learn about their water quality.

Q: What do you hope your K-State legacy will be?

Kirk: I would like my legacy to be centered on groundwater. Groundwater is the water source for 75% of Kansans and one of the most important resources for sustaining our future population and economic growth.

I want to create opportunities for students to develop careers managing and protecting this vital resource, and I want my research to help lay a foundation that others can build on and use to develop innovative solutions to water challenges.

###