The A to Z of VBPD

From African swine fever to mosquito-borne Zika, faculty collective attacks Kansas’ disease-carrying insects from every angle

ost Kansans probably don’t stop to ask if the mosquito they’ve swatted is Culex pipiens or Aedes albopictus. Nor do they look closely at the anatomy of a tick they’re pulling off to see if it’s Amblyomma americanum or Ixodes scapularis.

They’re bugs. Most people simply wish they weren’t there to begin with.

But even in the same families of insects there are significant differences in the risks and threats these vectors, or disease-carriers, pose for Kansas plant, animal and human health, and researchers at Kansas State University are combining their expertise to tackle these challenges.

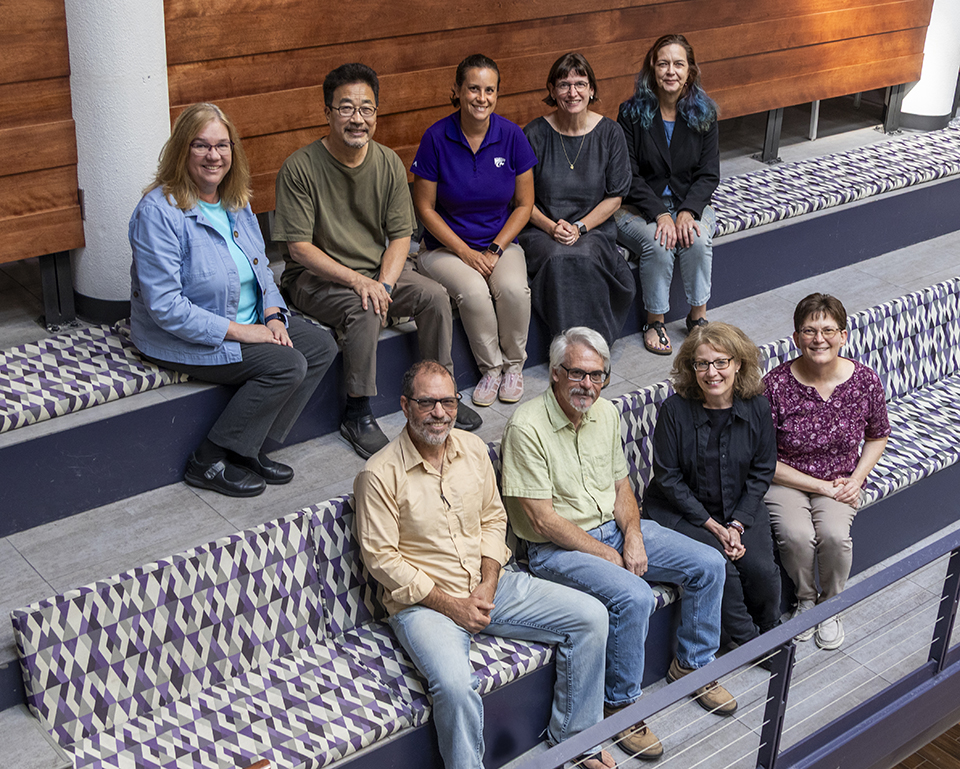

Using an award from K-State’s Game-changing Research Initiation Program, the Vector-Borne and Parasitic Disease, or VBPD, Collective is a cross-disciplinary coalition of faculty experts in insect and tick-borne disease and spread in obvious fields like biology, and its subdisciplines like virology, entomology and plant pathology, but also engineering, economics, geography, history, mathematics and nutrition education.

Every month, members of K-State's Vector-Borne and Parasitic Disease Collective meet to cross disciplines and discuss new ways to tackle some of the state's most pressing insect disease challenges. See a full listing of faculty members below.

Tackling vectors, parasites from all angles

Kristin Michel, professor of vector biology in the College of Arts and Sciences, and Dana Vanlandingham, professor of arbovirology in the College of Veterinary Medicine, lead the collective.

As part of the GRIP award, the collective has portioned out subawards to smaller teams, or even pairs, of researchers to carry out their vector-borne and parasitic disease work with the stipulation that they work outside their typical departments.

The result has been several cross-disciplinary projects developing innovative methods to study these vectors and the diseases they spread.

For example:

- Heather McCrea, associate professor of history, and Cassandra Olds, assistant professor of medical entomology, are working to analyze new insights from nearly century-old insect records.

- Yoonseong Park, university distinguished professor of entomology, Michael Chao, associate professor of animal sciences at Texas A&M, and Priscilla Brenes, extension nutrition assistant professor, are developing surveys to understand transmission and awareness of alpha gal syndrome at meat packing plants.

- Caterina Scoglio, university distinguished professor of electrical and computer engineering and Michel are working on applying engineering principles to identify how mosquitoes fend off infections.

- Vanlandingham and Douglas Goodin, professor of geography and geospatial sciences, are working to determine the impact of temperature, humidity and land-use in suburban backyards on mosquito species and abundance with the goal of understanding how microclimatic conditions influence different mosquito populations.

“These diseases are complex,” Vanlandingham said. “They involve insects, plants, animals, and people. They are influenced by landscapes and weather. So, to address these multifaceted challenges, we have to attack them from a lot of different angles.”

Mosquito matchup: The Asian tiger mosquito, left, has distinct white bands up and down its shiny black body and a white strip down its back. In comparison, the common house mosquito, right, is pale or light brown with no stripes. Asian tiger mosquitos are slightly smaller and active during the day, while common house mosquitoes are larger and tend to be more active at night.

The deadliest animal

Across their various fields, the researchers are studying vectors like ticks, biting flies and midges, but one point of emphasis is the mosquito — considered the deadliest animal to humans, across its various subspecies.

Between malaria, dengue, West Nile, yellow fever, Zika, chikungunya and lymphatic filariasis, mosquitoes kill more people worldwide than any other creature, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Ashmita Pandey, a doctoral candidate in Kristin Michel's lab, pipettes liquid food into a tray of mosquito larvae in the lab's insectary.

Although these diseases often only cause mild or moderate symptoms, they’re common enough around the world that even a fraction of cases becoming severe leads to hundreds of thousands of deaths each year.

Most of these diseases haven’t yet spread substantially in the U.S., thanks mainly to intensive control efforts in warmer states with climates similar to those of the tropical areas where these diseases are prevalent. Some, like malaria, were once common in the U.S. but were mostly eradicated in the mid-20th century.

Still, travel-related cases pop up by the thousands across the country each year, and warmer, wetter climates mean mosquitoes continue to pose a threat to public health, including in the Sunflower State.

When Michel first arrived in Kansas nearly two decades ago, the common house mosquito —Culex pipiens — and inland floodwater mosquitoes — Aedes vexans — were the most prevalent species in her backyard, she said.

But now, Michel most often sees Aedes albopictus, or the tiger mosquito — a hugely invasive species that is a vector for several concerning diseases.

“And we have seen it expand its range, especially in urban and suburban areas,” Michel said. “This species has been very opportunistic as it moves into new territory.”

Telling your ticks: The lone star tick, left, is reddish-brown, and females — which bite and feed longer and are more often found attached to a host — have a distinct, single white dot on their back. Blacklegged or deer ticks, right, are smaller and have shiny black legs that come off a dark — or in unfed females, orange or red — body.

Building surveillance

As the collective develops its preliminary investigations into larger projects, the researchers are building knowledge and a greater awareness of the need for vector-borne and parasitic disease research.

In the spring, the collective published a paper highlighting the significant economic impact vector-borne and parasitic diseases could have on Kansas livestock, agriculture and public health.

The report highlighted the need for updated data — most VBPD economic projections for this region rely on outdated impact models — and larger investment in surveillance and disease response infrastructure.

“And we have seen it expand its range, especially in urban and suburban areas,” Michel said. “This species has been very opportunistic as it moves into new territory.”

“These diseases are complex. So to address these multifaceted challenges, we have to attack them from a lot of different angles.”— DANA VANLANDINGHAM

Greater awareness, they hope, could lead to larger funding opportunities to support a new interdisciplinary center at K-State that would bolster the university’s work in the area through common training, combined infrastructure and enhanced collaboration.

The collective also hopes to establish a framework for an improved vector-borne disease surveillance system in Kansas modeled after those in other Midwestern states like Iowa and Wisconsin.

“If you want to know what’s circulating, the only way to get that level of understanding is through mosquito and tick surveillance,” Vanlandingham and Michel said. “It will take some funding to set up the infrastructure to support and expand the work of KDHE, but that cost is likely small compared to the potential consequences of even one severe case of West Nile disease.” ![]()

◊◊◊

Seek magazine

Seek is Kansas State University’s flagship research magazine and invites readers to “See” “K”-State’s research, scholarly and creative activities, and discoveries.