Little mouse on the prairie: What undergraduate research tells about big changes in Kansas nature

Sam Speck receives undergraduate honorarium from American Society of Mammalogists for research on changes in prairie mice communities.

Let Sam Speck tell you about the simple white-footed mouse and what it means for the future of Kansas ecology.

Let him explain how these small creatures signal major shifts in native prairie environments and are themselves important players as ecosystems change. Let him walk you through the implications of those changes, including an increase in ticks and related potential for disease in humans.

Speck, junior in conservation biology, Smithville, Missouri, is leading undergraduate research that tracks long-term changes in the types of mice found scurrying around the ground of the Konza Prairie Biological Station.

Through his work at the Long-Term Ecological Research, or LTER, site, Speck is uncovering new insights into how woody encroachment, or the takeover of native prairie grasslands by shrubs and trees, is affecting wildlife populations, with implications for human health.

It's impressive enough research that it earned Speck an undergraduate honorarium from the American Society of Mammalogists, one of the world's leading groups for the study of mammals.

"It's surreal that this group of important people doing amazing work around the world believes that my research is worthwhile," Speck said. "I have so much respect for the American Society of Mammalogists, and it's immensely gratifying to receive their highest award for an undergraduate student."

Students in K-State's fisheries, wildlife conservation, and environmental biology program get one-of-a-kind opportunities to learn fundamental concepts and modern approaches to studying organisms, populations, and ecosystems.

K-State transfer led to undergraduate research fieldwork

Speck wasn't even supposed to be a conservation biologist.

Ever since he was five, he knew he loved nature and wildlife, but by the time he was in high school, he was somewhat worried he wouldn't be able to make a career out of that passion, so he settled for studying accounting.

"That's when my parents sat me down and helped me realize that I needed to find a way to make it happen, to find a degree that could let me do the things I was passionate about while still setting me up for a successful career," Speck said.

After attending community college for a while, Speck transferred to K-State, where he started in the conservation biology program. That first fall semester, he took a Mammalogy course with Andrew Hope, associate professor of biology.

"K-State is uniquely situated to provide hands-on research experiences because it prioritizes faculty and teachers who are invested in connecting students to these career-building opportunities."

Speck remembers being enthralled by all the research opportunities Hope talked about in class. At the end of the semester, Speck emailed Hope to see how he could get involved. He ultimately got a job curating specimens in the Kansas State Biorepository, a museum on campus that preserves mammals and their parasites for enhancing both research and educational opportunities.

That first job also involved doing DNA extractions in a laboratory setting, and Hope soon helped Speck get involved in field work at the LTER site at Konza.

"Honestly, I didn't even know what the LTER was when I first got to K-State," Speck said. "So when I first went out there, I was in shock. There's a palpable energy to the Konza that you feel when you're out there, especially when you're walking a trap line and collecting samples. Even when you're by yourself and there's no one around for miles, it's a moment of isolation that doesn't quite make you feel alone because there's still so much happening around you."

Woody encroachment and prairie mice trends

As Speck became more involved in the research, he eventually joined a project that started with analyzing decades of data collected at the LTER for the types of mice being caught in traps at the site.

"In the field, we were starting to see way more of the white-footed mouse, and that wasn't the case even 10 years ago, when the deer mouse was still more abundant," Speck said.

That was significant because the white-footed mouse is more commonly found in wooded or shrubby areas, while the deer mouse has traditionally been more typical in prairie grassland environments.

Speck's next step was to combine his ongoing observations of changing small mammal communities with data showing increasing densities of both mice and ticks. He then worked with Zak Ratajczak, assistant professor of biology, to combine that with plant datasets to relate trends in mammals and ticks with changing vegetation.

They found that in woody or shrubbed areas on the Konza Prairie that have not been burned frequently, there has been a substantial transition from the deer mouse to the white-footed mouse, primarily because of woody encroachment on the different watersheds of the prairie.

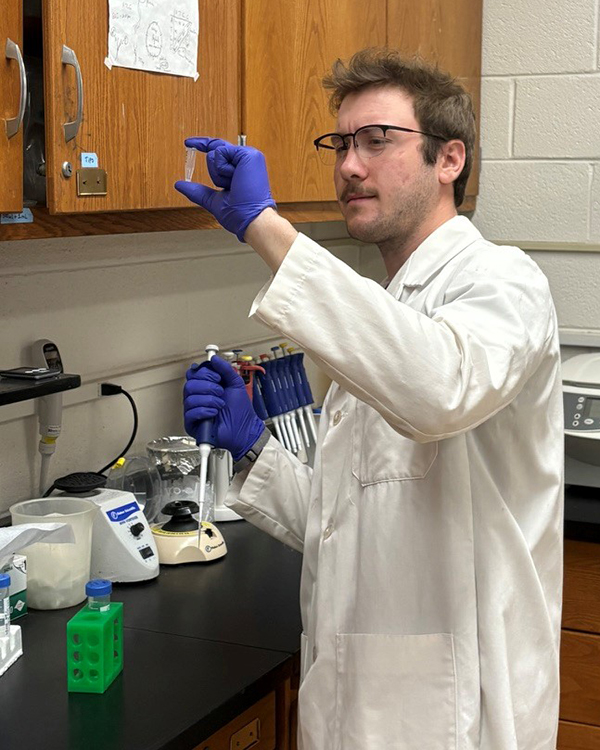

Sam Speck, junior in conservation biology, is leading undergraduate research on trends in prairie mice community genetics that show broader changes in the grassland ecology.

"With that comes increases in zoonotic disease risks for humans, " Speck said. "The white-footed mouse can carry many kinds of diseases that can then be transmitted to humans. As densities of both mice and ticks become more abundant in woodland areas, so does the potential for disease."

These mice are closely associated with the ticks that carry Lyme disease, and Kansas has started to see more reported cases of Lyme disease every year. The research data suggests that could be connected to the increases the region is seeing in the woodland mouse, compared to the prairie mouse.

The samples collected and preserved in the museum are a record of long-term changes in the local biodiversity and habitats of the Konza Prairie, throughout the state of Kansas and further across the Great Plains. The researchers were able to compare Konza data to historical data from specimens held in natural history museums across Kansas, observing many of the same trends with mice populations around the state, especially in areas where prairie burns have become less frequent.

Speck’s findings are currently being considered for publication in the journal BioScience.

He was one of K-State's representatives earlier this spring when he presented his work at Undergraduate Research Day at the Kansas State Capitol.

"We take mice for granted, mainly because they're so abundant everywhere," Speck said. "But because of that, they're actually an excellent way to study the underlying ecological mechanisms in an environment. It's kind of cool that this one little mouse can tell you so much about what's going on in the broader scheme of nature."

Making a difference through parasite research

This summer, Speck will travel to the American Society of Mammalogists' annual conference in Purdue, Indiana, where he will present his research.

"The research that Sam is involved with is of high impact because it builds scientific linkages between long-term ecological research data and specimen resources within museums, all towards human health outcomes," Hope said. "This is pretty new, and opens up lots of opportunities for more student research into the future. Sam’s keen interest in studying the relationships between parasites and their mammal hosts is a great starting point for a successful trans-disciplinary career, and this award from ASM is a deserved recognition of that commitment."

Through his experiences, Speck said he has found a passion for parasitology, a field where he believes he can make a big difference.

"I want to do research that impacts people in a way that matters," Speck said. "Parasitology is a field where I think I could do that. Here in the U.S., we don't feel the effects of parasites as much, but around the world, millions of people suffer from the effects of parasites. I'd love to be able to work in that field and maybe even one day come back to K-State as a professor."

That ambition will take hard work, but Speck knows he is at the right place with the right support and the right people to get him to his doctoral degree.

"K-State is uniquely situated to provide hands-on research experiences because it prioritizes faculty and teachers who are invested in connecting students to these career-building opportunities," Speck said. "I've had so many of those here, and it's helped me build a resume that is going to set me apart as I pursue my dream."

###

Media contact: Division of Communications and Marketing, 785-532-2535, media@k-state.edu

News tip: Smithville, Missouri.

Website: k-state.edu/hopelab/

Photo available: Sam Speck, junior in conservation biology, is receiving a prestigious undergraduate honorarium from the American Society of Mammalogists for his undergraduate research on changes in prairie mice communities. | Download this photo.

Notable quote: "We take mice for granted, mainly because they're so abundant everywhere. But because of that, they're actually an excellent way to study the underlying ecological mechanisms in an environment. It's kind of cool that this one little mouse can tell you so much about what's going on in the broader scheme of nature." — Sam Speck, junior in conservation biology.

Written by: Rafael Garcia, 785-532-2535, rafagarc@k-state.edu