Lesser Prairie-Chicken and Grassland Response to Intensive Wildfire in the Mixed-Grass Prairie

Investigators:

Dan Sullins, Ph.D. student

John Kraft, M.S. student

Matthias Sirch, B.S. student

Nick Parker, M.S. student

Project Supervisors:

Dr. David Haukos

Funding:

USDA NRCS

LPCI

Pheasants Forever

Kansas Department of Wildlife, Parks and Tourism

Cooperators:

Kansas Department of Wildlife, Parks and Tourism,

USDA, Lesser Prairie-Chicken Initiative

Location:

Clark County, KS

Completion:

December 2020

Status:

Completed

Objectives:

Assess changes in vegetation and LEPC habitat availability

Assess LEPC resource selection in response to extreme wildfire

Estimate the influence of extreme wildfires on LEPC population demography

Progress and Results:

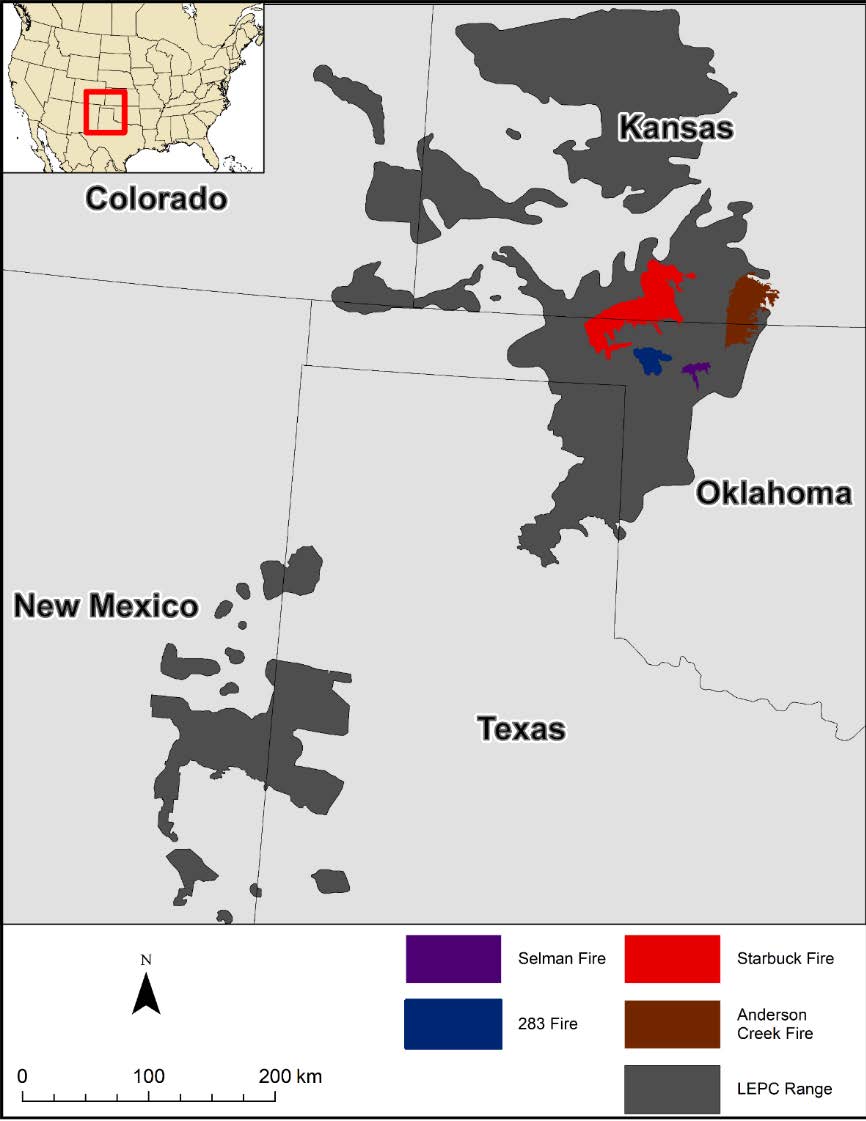

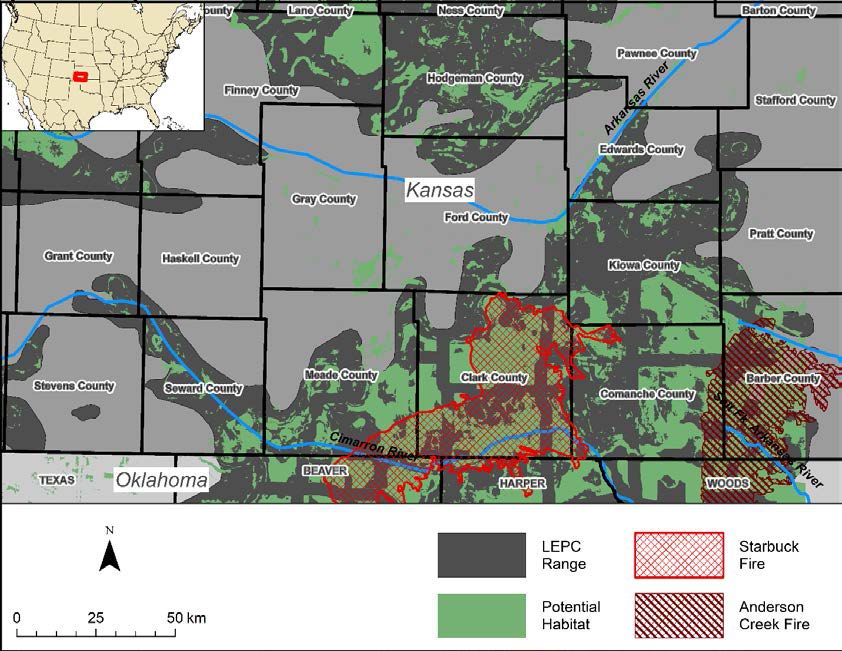

Large intensive wildfires (>100,000 ha) have burned substantial portions of the lesser prairie-chicken (Tympanuchus pallidicinctus) range over the last three years. The Starbuck fire burned 2,521 km2 (623,000 acres; Figures 1 and 2) of mostly grassland and encroaching woodland in Beaver and Harper counties, Oklahoma, and in Meade, Clark, and Comanche counties, Kansas, from 7 March to 12 March 2017 (inciweb.org 2017). The wildfire was the largest on record for Kansas (Kansas Forest Service) and the area burned was all within the lesser prairie-chicken distribution. Fire is an important ecological disturbance that formerly played an important role in maintaining grassland habitat for wildlife. However, response of lesser prairie-chicken populations and the habitats they occupy to extreme wildfires are unknown.

Knowledge on the effects of extreme wildfire on lesser prairie-chickens is needed because (1) lesser prairie-chickens populations are confined to a few large relict grasslands within the Great Plains where population persistence may be more susceptible to widespread stochastic events; (2) lesser prairie-chickens populations have shown long-term population declines and are a species of conservation concern; (3) effects of extreme wildfire on lesser prairie-chickens are not readily apparent (e.g., tradeoffs of burning nesting habitat or woody areas); and lastly, (4) the timing of the fire presents a unique opportunity for a Before-After-Control-Impact study design because extensive data were collected within the area burned before the fire from March 2014–March 2016.

Methods:

Lek count and photo point data were collected immediately following the fire in the spring of 2017. After receiving funding from the USDA and setting up a field house in 2018, we collected more photo point and lek count data, and initiated capture of 23 lesser prairie-chickens that were marked with GPS transmitters. We also conducted vegetation surveys, raptor surveys, and monitored reproduction, resource selection, and survival of marked lesser prairie-chickens. We will continue data collection until the end of February 2020 and will capture birds in the spring of 2019.

To assess changes in vegetation and lesser prairie-chicken habitat availability, quality, and distribution, we conducted 250-m point-step surveys estimating species composition in the spring/summer of 2018 (Evans and Love 1957). Grassland structure were estimated at 50-m intervals throughout the point-step transects based on visual obstruction following Robel et al. (1970). Estimated composition was related to user-defined cover types (patches) that are greater than 5 ha in size and relatively homogenous in appearance (Plumb 2015). In addition to point-step transects, vegetation composition and structure were also estimated at random locations distributed throughout patches (10 point per ~120 patches). At each point location, visual obstruction, percent horizontal cover of functional groups (grass, forbs, shrubs, bare ground, and litter), litter depth, and 3 dominant plant species within a 4 m radius of the location data were collected following Sullins (2018).

In addition to field collection of data, we also used remote sensing tools to assess burn severity and examined remote sensing options for estimating tree canopy cover change post fire.

Results:

Photo Points

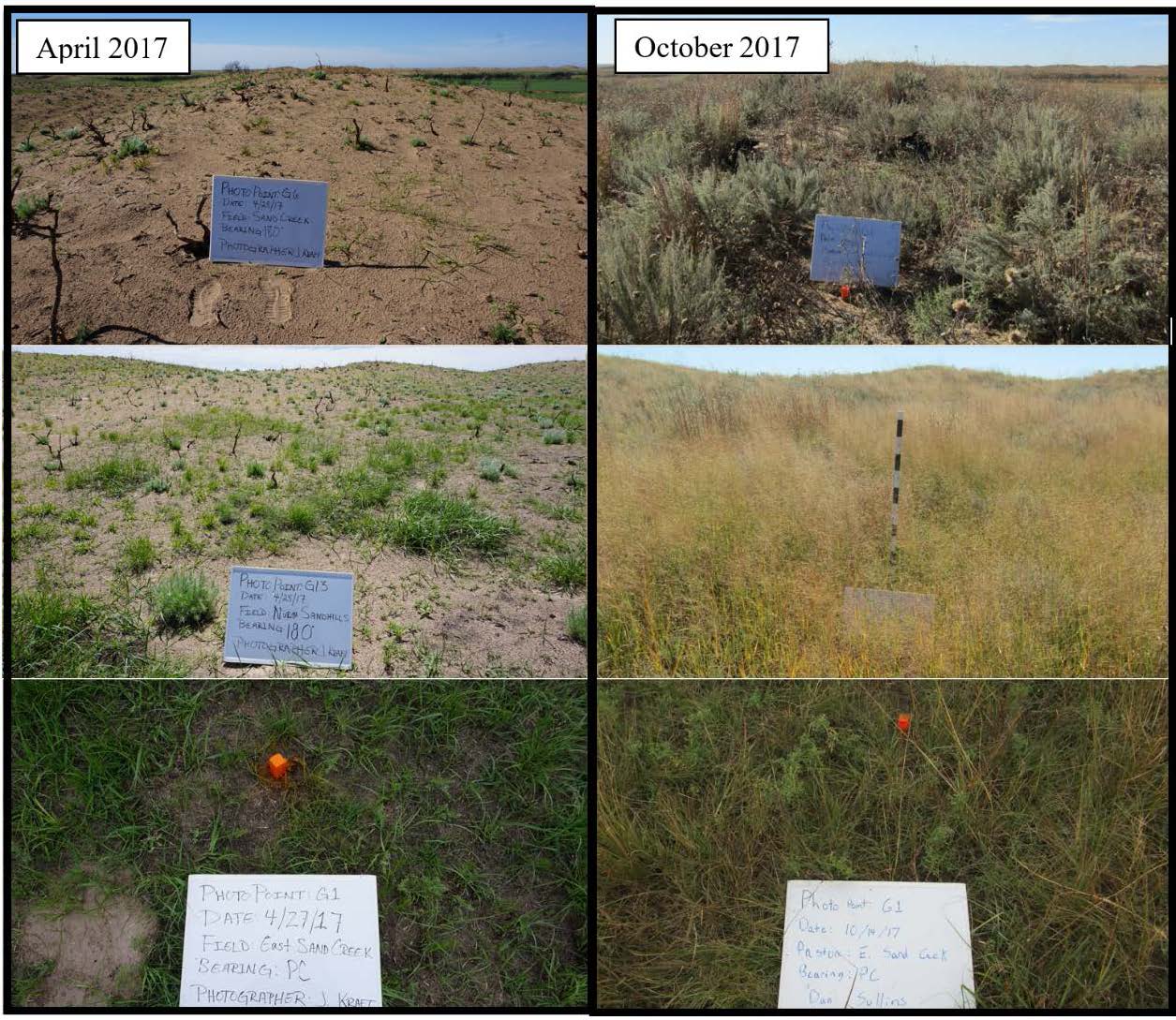

We took photos at identical locations (n = 16) spanning ecological sites on the study area and with the same bearing in April and October of 2017, and April 2018. An example of photo points is shown in Figure 3. At each location a phot was taken looking directly downward and facing North, East, South, and West.

Lek Counts

Table 1. Maximum number of males counted on leks before the fire in 2015 and after the fire in the spring of 2018 in Clark County, KS.

| LEK |

Before 2015 |

After 2018 |

| GAR2 | 20 | 0 |

| GAR3 | 4 | 0 |

| GAR4 | 4 | 5 |

| GAR5 | 18 | 0 |

| GAR6 | 11 | 2 |

| GAR7 | 8 | 0 |

| GAR8 | 13 | 3 |

| GAR9 | 9 | 0 |

| GAR10 | 20 | 20 |

| GAR11 | 17 | 9 |

| GAR12 | 22 | 4 |

| GAR13 | 7 | 1 |

| Seacat* | 9 | |

| WIHA | 11 | 14 |

| Total | 164 | 67 |

| *did not observe lek in 2015 | ||

Capture

We captured birds during 59 events and captured 43 unique lesser prairie-chickens during the lekking period in the spring of 2018. Of the 43 lesser prairie-chickens, 10 were female and 39 were male. We marked 9 females and 13 males with GPS satellite transmitters to monitor movements, reproduction, and survival. Notable recaptures included two males that were banded in 2014 and one from 2015. One of the recaptured males was at least 5 years and 10 months old.

Vegetation Surveys

During the spring and summer of 2018, we collected point vegetation data at 2 randomly selected location for each marked lesser prairie-chicken per week and at 1,172 random locations distributed throughout the burned area and on an unburned area north of the main study site in 2014–2015. We also conducted 302 250-m point-step surveys to estimate species composition within unique grassland patches and fields.

Reproduction

We monitored a total of 9 nests in spring/ summer of 2018 with attempted nests from 8 of the 9 marked female lesser prairie-chickens and 2 females re-nesting after failed first attempts. Of all the monitored nests, only 2 hatched. Of the 2 successful nests, 1 was confirmed by checking nest and flushing 7 day old chicks, the other nest was determined successful based on remote monitoring of GPS locations. We were denied permission on the nest that was monitored remotely and could not ground truth the successful nest or monitor the brood. We were able to monitor the other brood to 14 days old. Three chicks survived to 14 days old but were not detected during later brood flushes. We expect that an intense hailstorm on 6/24/18 killed the chicks.

Nests were initiated from 5 May 2018 – 10 June 2018 which was later than nest initiation in 2014 and 2015 before the wildfire. We expect that the lack of precipitation from October 2017 to mid-April of 2018 may have delayed nesting. Of the nests that failed, 5 out of 7 were depredated by snakes with the remaining depredations by mammals. The predator of the final failed nest was not confirmed. The high rate of snake depredation was not expected, however, snakes may benefit from exposed bare ground following fire and are can avoid fire by using burrows in early spring (Russell et al. 1999).

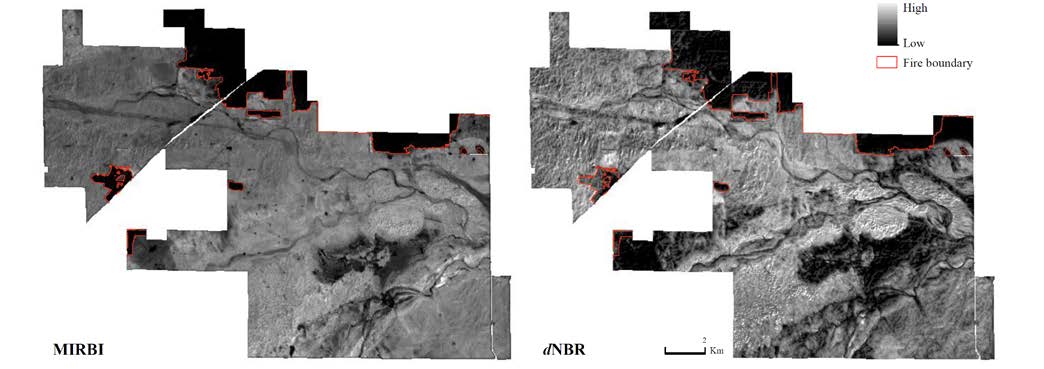

Remote Sensing of Burn Severity and Tree Canopy Cover Change

We estimated burn severity from Landsat 8 imagery using a Mid Infrared Burn Index (MIRBI) and a Normalized Burn Ratio (dNBR). We will use the burn severity classification to assess the effect of fire severity on lesser prairie-chicken use of the landscapes. We are currently working to estimate the distribution of trees on the study area remotely to assess the impact of the fire on canopy cover change.

Figure 1. Notable fire perimeters in the Mixed Grass Prairie Ecoregion of Kansas and Oklahoma in 2016 (Anderson Creek) and 2017 (Starbuck, 283, and Selman; McDonald et al. 2014). The Proposed research efforts will focus on areas impacted by the Starbuck fire which burned from 7 March – 12 March 2017. The presumed range of lesser prairie-chickens is also shown (Hagen and Giesen 2005).

Figure 2. Perimeter of the Starbuck and Anderson Creek fire in the Mixed Grass Prairie Ecoregion of Kansas, estimated potential habitat from Sullins (2017), and the presumed range of lesser prairie-chicken from Hagen and Giesen (2005). Post fire research will focus on the Clark County portion of the Starbuck fire.

Figure 3. Photo points collected in Clark County, Kansas, on the Gardiner ranch in April 2017 (a month after the fire) and in the following October 2017. Photos on the left are from the same location and facing the same direction as photos on the right.

Figure 4. The Mid Infrared Burn Index (left) from March 8, 2017, and Normalized Burn Ratio (right) from March 1 and 8, 2017, calculated using Landsat 8 imagery downloaded from the USGS Earth Explorer website.