On a molecular level

Undergraduate researcher investigates the potential of nanoporous materials

By Kate Kennedy

Erin Frenk fell in love with science during her first experiment at age 14. She loved gathering data, the uncertainty of end results and, most importantly, asking and answering her own questions.

Erin Frenk fell in love with science during her first experiment at age 14. She loved gathering data, the uncertainty of end results and, most importantly, asking and answering her own questions.

Frenk, a Kansas native and junior in chemistry, said she initially set her sights on colleges across the country but ultimately fell in love with Kansas State University and the opportunities it presented.

“The programs are great and the faculty in the chemistry department are welcoming,” Frenk said. “Chemistry was a perfect avenue because the curriculum allowed me to pursue many different research paths, and I knew I could start undergraduate research early.”

Less than a year later, Frenk was introduced to an analytical chemistry lab run by Takashi Ito, professor of chemistry in the College of Arts and Sciences.

Ito’s lab is developing methods that utilize electrochemistry, the study of electrical potential and chemical changes, to create and deposit nanoporous materials. These materials contain pores of nanoscale size and can detect and remove specific chemicals related to environmental and energy sciences.

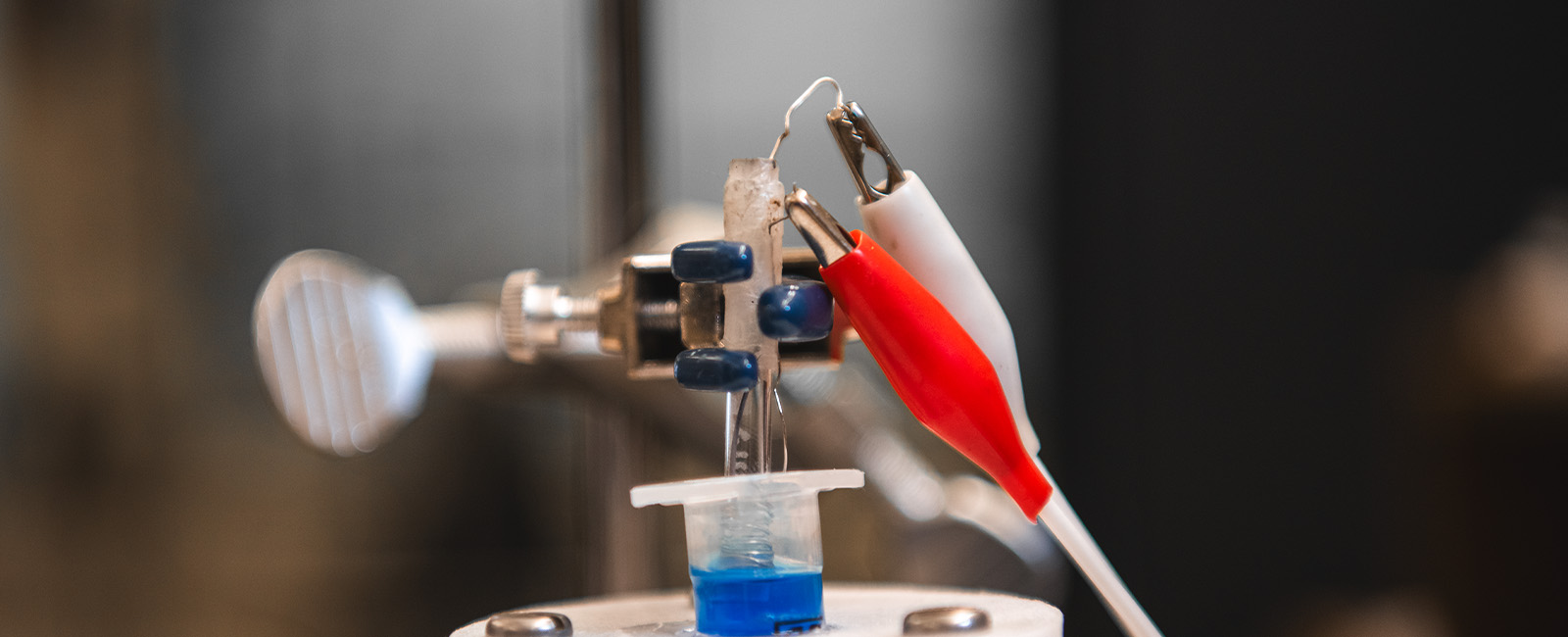

Frenk utilizes a potentiostat — an instrument that controls electrodes — to apply negative voltage through an electrode in a solution and deposit a small film of metal-organic frameworks onto a surface. The metal-organic frameworks are uniform and cage-like structures formed by metal ions held together by organic linkers. Frenk specifically investigates the cathodic growth — a reaction where an electrode accumulates electrons — taking place when the metal-organic framework films are deposited onto a graphite slate.

“Literature has shown the preparation of uniformly thin metal-organic framework films with controlled thickness and crystal orientation to be difficult,” Frenk said. “By controlling the applied potential, electrochemical methods have successfully been used to control the thickness of these thin films.”

Frenk explained improving the methods of creating metal-organic framework films has gained recent attention, as they can capture carbon dioxide and remove toxic chemicals from water.

Frenk’s goal is to one day work in environmental science.

“My research has many environmental applications, but right now, learning how to think like a scientist is the most important lesson I am taking from my research,” she said. “I am passionate about taking care of our environment, but what I am doing right now is helping me develop a foundation to become a better researcher.”

Frenk’s passion for her work is made more evident by her academic timeline, as she is on track to complete a five-year accelerated program at K-State in just four years and graduate with a bachelor’s in chemistry and a master’s in business administration.

This summer, Frenk hopes to continue her work with researchers at Argonne National Laboratory and eventually join a graduate program to study environmental or materials science.