Researchers build on infrastructure investment

Improving the framework

By its very nature, infrastructure is often overlooked. Most of the time, it is only when a system fails that infrastructure gets the attention it deserves. Bridge collapses, boil advisories and damaging severe storms serve as periodic reminders that life is much harder when the power is out or roads are closed.

But breakdowns aside, it doesn’t take close examination of the way our society is built and functions to quickly realize how critical infrastructure is to a thriving civilization. It is a reality that many Kansas State University researchers know and understand.

It’s a reality that has generated congressional attention, too. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act passed in 2021 included nearly $550 billion to rebuild America’s roads and bridges while delivering clean water and building robust broadband networks in communities that previously lacked access. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 provided another $500 billion to boost the green energy sector and reduce the nation’s carbon footprint.

Combined, the two laws represent a level of investment in the nation’s infrastructure not seen since since the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, which created the country’s interstate highway system.

But this newest funding isn’t just for use on bridges and roads. Some of the money is allocated toward research that could change the way we build things, the way we travel and even the way we make decisions. That’s where the Carl R. Ice College of Engineering at K-State is ready to step in.

The challenge of Kansas infrastructure

Anyone who has driven on Interstate 70 from Wyandotte County all the way to Sherman County knows that Kansas is not a small state. With more than 81,000 square miles for a population of fewer than 3 million people, Kansas ranks as the 13th largest state by area in the U.S., but has the fourth highest number of miles of road behind the much more populous states of Texas, California and Illinois. The state also ranks among the top five in number of bridges, many of which are in desperate need of repair, researchers say.

“It goes back to the U.S. Public Land Surveying System — a grid system,” said Eric Fitzsimmons, George Yeh — Carl and Mary Ice Keystone research scholar and Hal and Mary Siegele professor in engineering. “Kansas land is still made up of squares, so almost every mile of land has a road surrounding it, whether it’s dirt, gravel or paved. So, Kansas has more than 140,000 miles of roadways, 126,000 of which are in rural areas, which ranks No. 2 in the country.

“It goes back to the U.S. Public Land Surveying System — a grid system,” said Eric Fitzsimmons, George Yeh — Carl and Mary Ice Keystone research scholar and Hal and Mary Siegele professor in engineering. “Kansas land is still made up of squares, so almost every mile of land has a road surrounding it, whether it’s dirt, gravel or paved. So, Kansas has more than 140,000 miles of roadways, 126,000 of which are in rural areas, which ranks No. 2 in the country.

“The challenge is that you have a significant amount of infrastructure and a limited tax base for funding the repairs through state funds.”

Fitzsimmons and his colleagues in the civil engineering department are addressing this challenge by finding better ways to build bridges and roads, from improved design to more economical materials, all on actionable timelines.

“One of the things that’s unique about what we do is it’s very applied research,” Fitzsimmons said. “It’s about delivering fast, deployable results for Kansas — many times without the traveling public even knowing.”

Fitzsimmons also focuses on highway vehicle safety. He’s working with Doina Caragea, Don and Linda Glaser Keystone research scholar and professor of computer science, on a project that uses machine learning to determine the underlying factors that affect the likelihood of commercial motor vehicle crashes in Kansas.

“If you can predict commercial motor vehicle crashes, you can direct the Kansas Highway Patrol on where to enforce and allocate resources,” Fitzsimmons said. “Using advanced tools and the vast amounts of data collected by multiple agencies in Kansas, we are hoping to save the time and resources of police officers.”

Additionally, Fitzsimmons and his colleagues at the K-State Olathe campus received funding from the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration to host the second Midwest Commercial Vehicle Safety Summit in Kansas City, Missouri, in November 2023. The summit brings together a diverse group of transportation stakeholders, the federal government and academic researchers who all share the same interest of seeing increased safety and fewer crashes involving large trucks and buses on Midwest roadways.

Infrastructure resilience

For Bala Natarajan, the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic also provided an opportunity.

For Bala Natarajan, the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic also provided an opportunity.

Natarajan, the Clair N. Palmer and Sara M. Palmer professor of electrical engineering, had an idea for a research project focused on infrastructure resilience that also considered the human element of these decisions.

But he needed a team. So, stuck at home like everyone else, he picked up the phone and began cold calling academics across the state, asking for 20 minutes of their time and pitching his idea to anyone who would listen.

“When I started thinking about resilience from this holistic standpoint, I didn’t know anyone working on this,” said Natarajan, also a Steve Hsu Keystone research scholar in the Mike Wiegers Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering.

His strategy led to a project titled “Adaptive and Resilient Infrastructures driven by Social Equity,” or ARISE. The project is funded through a National Science Foundation Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research, or EPSCoR, RII Track-1 grant. The final $24 million award involves 17 institutions, including the University of Kansas, Wichita State University and many other four-year and community colleges throughout the state.

Seven K-State researchers are collaborating on the project, including Natarajan; George Amariucai and Lior Shamir, both from computer science; Husain Aziz, civil engineering; Anil Pahwa, electrical and computer engineering; Vaishali Sharda, biological and agricultural engineering, and Jason Bergtold, agricultural economics.

The project centers on advancing the resilience of various forms of infrastructure across Kansas by creating tools that support the most vulnerable, while also helping communities use these tools to make informed decisions on investment and management of infrastructure in the future.

Natarajan said the group was focused on social equity because the most socially vulnerable people often live and work in the most physically vulnerable locations that typically receive less attention from an infrastructure perspective.

The researchers are already a year into developing various models and simulations to help solve these problems and have worked with several communities to help guide their decision-making, with more expected in the coming months and years.

The researchers are working with partner communities that are diverse and face different challenges related to disaster resilience. The partner communities include Ford, Finney and Seward counties in southwest Kansas and Wyandotte and Johnson counties in the east.

In this way, the timing of the federal government’s generational investment into infrastructure couldn’t have been better.

“This is unprecedented,” Natarajan said. “We are not going to see again, in our lifetimes, an investment like this from the federal government on infrastructure. The question is how do we help our communities get some of it?”

While the ARISE program isn’t contributing capital to fund building projects or repairs, it is partnering with local governments and leaders to capitalize on funding opportunities from the two congressional bills.

“I realized that we, as universities, can partner with these communities and help them write grants and proposals to actually implement the ideas that we are developing through the project,” Natarajan said.

The team’s size and diversity are some of its strengths. Experts across disciplines — from behavioral science to water quality to transportation — work together and combine resources, resulting in models that help both rural and urban communities across Kansas thrive. Since the data is from real communities, the group is creating a synthetic city that combines all of the team’s research, which creates accurate and realistic models and allows the results to be published in academic journals and other outlets.

“Since this is actual critical infrastructure, we can’t reveal much of the community data publicly,” Natarajan said. “But we want to do fundamental research that can be published. The synthetic city is something we’re still in the process of building. That portion has been a pretty interesting experience on its own.”

Reducing emissions, powering the future

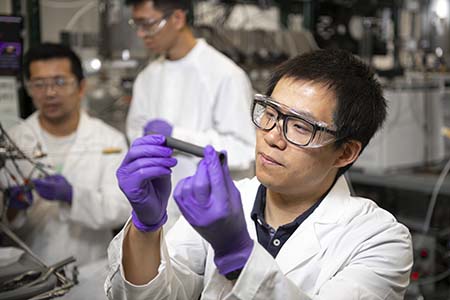

Chuancheng Duan, assistant professor in the Tim Taylor Department of Chemical Engineering, has been busy since his arrival at K-State in 2020.

Chuancheng Duan, assistant professor in the Tim Taylor Department of Chemical Engineering, has been busy since his arrival at K-State in 2020.

Duan’s Materials Research Laboratory for Sustainable Energy aims to create materials and devices that convert and store energy with the goal of addressing critical energy and environmental issues. He has been awarded more than $5 million in research funding from a variety of organizations and industry partners, including the U.S. Department of Defense and NASA. In the last year alone, he’s secured more than $1.7 million in funding from the U.S. Department of Energy for his work. Duan studies a variety of devices that increase efficiency or create new high-value chemicals as part of emissions reduction in large industrial engines, such as those used in power plants.

Think of a catalytic converter in a vehicle, but on a much larger scale. The engine exhaust material is fed through the converter, which reacts with the catalysts inside and results in a less-damaging fume that is then released into the air through the exhaust pipe.

Duan is designing devices that operate similarly but on large-scale industrial combustors fueled by natural gas. One project focuses on cutting waste related to stranded natural gas, which is fuel that has been discovered but is economically unusable because of the expense of additional pipelines or other forms of transport. This fuel is often burned because of a lack of better options. Duan’s device would take that exhaust and create electricity from the burning of the natural gas, and also create liquid fuel that is far simpler and more efficient to transport and use.

“We use the natural gas, we don’t release carbon dioxide and we produce high-value chemicals all at once,” Duan said.

Similarly, Duan’s largest project focuses on creating a device that functions like a catalytic converter and can be attached to existing natural gas-powered engines. The goal is to increase efficiency and reduce the amount of methane released into the atmosphere by converting the exhaust into hydrogen and carbon dioxide. The carbon dioxide is a less potent greenhouse gas for environmental purposes, while the hydrogen created is a valuable commodity.

“This kind of technology will be very important for the future,” Duan said. “That’s why the Department of Energy is investing almost $8 billion into hydrogen technology, and I think in the next five to 10 years, there will be significant change to the hydrogen economy in the U.S.”

Duan’s lab also is researching the development of fuel cells that could replace battery technology in a variety of devices, from electric vehicles to whole-home generators to a mobile power source used by soldiers on long field missions.

One of his projects, partially funded by the U.S. Army Research Laboratory, looks at the mobile power source issue.

“A big battery also works, but it’s extremely heavy,” Duan said. “Gasoline-powered generators create too much noise, but the fuel cells we’re developing are quiet and can create power from electrochemical reactions and can be powered from a variety of fuel sources, like a small propane tank you’d use for a barbecue. It can provide reliable, efficient electricity for the military.”

But Duan also is interested in the development of vehicle fuel cell technology. Vehicles fueled by hydrogen are already on the road in a limited capacity in California, but the lack of a network of fueling stations makes these vehicles impractical for widespread adoption nationwide. Duan has several projects funded by Nissan Motor Co. Ltd. and Nissan North America Inc. to bring his fuel cell technology into production for potential use in its fleet.

“The materials that are catalyzing inside of the fuel cell are compatible with many kinds of fuel,” he said. “It can use ethanol, natural gas, propane or even gasoline. You can go to the same gas station as always to fuel, but using a fuel cell powered vehicle, you’re going to see significantly increased efficiency, something like 50 miles per gallon instead of 20.”

So, will the electrical charging network infrastructure being developed for electric vehicles be made obsolete by fuel cell powered vehicles that use hydrogen or other types of renewable fuels in the future? Duan says no.

“All you need to create hydrogen is water and electricity,” he said. “The infrastructure being built for current electric vehicles can also be used to produce hydrogen in the reversed mode of a fuel cell, which is the electrolysis cell.”

Read more about infrastructure-related research at K-State.