In challenging times, K-State researchers step up to help farmers

Risk and reward

By Pat Melgares

Kansas agriculture facts from the Kansas Department of Agriculture

U.S. Department of Agriculture Risk Management Agency

U.S. Drought Monitor for Kansas

Ogallala Aquifer Program

Kansas High Plains Aquifer Atlas

Nature Communications article: “Using insurance data to quantify the multidimensional impacts of warming temperatures on yield risk”

Say this about modern-day farmers: They’re a resilient bunch. They have to be. Surviving in a business that feeds billions of people worldwide includes navigating the uncertainties of weather, fluctuating prices, natural disasters, environmental regulations, crop pests, livestock diseases and more.

Say this about modern-day farmers: They’re a resilient bunch. They have to be. Surviving in a business that feeds billions of people worldwide includes navigating the uncertainties of weather, fluctuating prices, natural disasters, environmental regulations, crop pests, livestock diseases and more.

“The key lies in the meaning of life,” said Mark Gardiner, who owns Gardiner Angus Ranch in Ashland, Kansas, with his family. “As farmers, we are fortunate to have this life. All walks of life have strife. You can choose to live or die. We choose to live and be thankful. Like many before us and after us, you get back up and go to work one step at a time.”

Six years ago — on March 6, 2017 — Gardiner narrowly escaped as a devastating wildfire swept through much of southwest Kansas and northwest Oklahoma. Known as the Starbuck Fire, the wind-whipped blaze torched an estimated 800,000 acres in the two states, including 480,000 acres in Clark County, Kansas.

In the aftermath, the fire’s devastation was unmistakable across the region as well as at the Gardiner Angus Ranch, where 44,000 of the farm’s 48,000 acres had burned, taking along with it 600 cows, 270 miles of fence, 7,500 large bales of hay, several implements and farm structures, and Mark Gardiner’s family home.

Most other challenges of today’s farm families are less sudden. But they can be just as harsh. It’s a reality that Kansas State University aims to ease through research focused on helping people like Gardiner as they navigate the modern-day farm.

Navigating risk

The Kansas Department of Agriculture lists agriculture’s economic impact in the state at $76 billion, supporting more than 256,000 jobs — about 14% of the state’s workforce. Kansas has more than 45 million acres of farmland, which makes up 87.5% of all Kansas land. More than 21 million acres are harvested for crops and 14 million are for grazing animals.

The Federal Crop Insurance Corp. reported that Kansas farmers were paid more than $1.8 billion in 2022 to cover losses in crop production. But that only takes into account those who grow crops, and only those who had purchased crop Insurance.

“You never really get away from risk in this business, but if you take care of that side of your operation properly, and have crop insurance, well then you’ll still be here to play another year,” said Pat Janssen, who farms near Dodge City.

In the K-State College of Agriculture, agricultural economists, too, have helped farmers build their safety net. As one example, Edward Perry and Jisang Yu, both associate professors, and Jesse Tack, professor, reported findings of a 2020 study that indicated a 1 degree Celsius increase in temperature was associated with farmers’ yield risk increasing by approximately 32% for corn and 11% for soybeans — two major crops in Kansas.

Yu said production losses linked to drought are even larger than those linked to heat — and larger still in instances where heat and drought are combined.

That information is important to farmers’ annual decisions on such input costs as seed and fertilizer, based on their yield goals. Tack notes that when forecasts indicate the likelihood for increased heat and drought, producers may devote fewer inputs to production — much like investors shy away from risky stocks.

Yu describes his research as examining the production impacts of crop insurance and the effect of weather on the “riskiness of farming.”

“For farmers, the most important element in the context of risk management is to have a clear objective so that they can optimize production accordingly,” Yu said.

“I would liken farming to a chess match rather than gambling,” Janssen said. “Through strategic planning and having a plan for six months or even two years down the road, you can mitigate a lot of risks.”

Drought hits hard

Few topics raise eyebrows in farm country like water, especially having enough of it. For most of the past decade, farmers raising crops on dryland, or nonirrigated, acres have labored in drought, often hoping that all-too-infrequent rains will come at just the right time when crops can use it.

Chip Redmond, manager of the Kansas Mesonet, which is a K-State network of weather stations, said defining drought is difficult. The National Integrated Drought Information System, a program administered by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, has more than 150 definitions of the word.

The definition that seems to stick: “A deficiency of precipitation over an extended period of time … resulting in a water shortage.” Agricultural drought happens when crops and livestock are affected.

In any case, drought affects most of Kansas. As of January 2023, the U.S. Drought Monitor listed 87 of the state’s 105 counties with U.S. Department of Agriculture disaster designations, which affects just under 2 million people — two-thirds of the state’s population. The same agency lists 2022 as the 17th driest year on record, based on 128 years of Kansas data.

For nearly a dozen years, K-State researchers have been getting ahead of some drought concerns by conducting research in other countries where semi-arid and drought conditions are the norm. The university currently hosts four projects — called Feed the Future innovation labs — funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development.

These labs address important drought-related issues, such as growing crops — sorghum, millet and wheat —that rely less on irrigated water; sustainability and increasing productivity without damaging the environment; and wheat genetics. Another university innovation lab addresses post-harvest food losses. Together, the four labs conduct work in 12 countries and three continents.

“We work in the Sahel region across the entire African continent from Senegal to Ethiopia,” said Tim Dalton, director of K-State’s Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Collaborative Research on Sorghum and Millet. “One major issue we have is to improve heat and drought tolerance of sorghum and millet grown in these regions. Insight on what works there is relevant for Kansas and is one of the clearest examples of why global cooperation is so important.”

“As we’ve seen the past year with the war in Ukraine, nobody has the benefit of being completely isolated by local decisions in agriculture,” said Susan Metzger, director of the Kansas Center for Agricultural Resources and the Environment at K-State. “Being connected to not only the exchange of commodities, but also having a community that exchanges knowledge and discovery is so incredibly important.”

Jonathan Aguilar, an irrigation engineer at K-State’s Southwest Research and Extension Center in Garden City, said in-state studies to manage water more effectively are a major focus of many K-State Research and Extension activities in western Kansas.

“One area in which K-State can help farmers is on how to prepare their currently irrigated land to dryland farming while they still have access and infrastructure for irrigation water,” said Aguilar, also an associate professor in the Carl and Melinda Helwig Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering in the Carl R. Ice College of Engineering.

K-State researchers have been national leaders in drip irrigation technology, a system of hoses either on or below the ground to deliver water and nutrients directly to the plant’s root zone. Aguilar and a team recently completed a project on the feasibility of implementing mobile drip irrigation — in which polyurethane tubes similar to garden hoses are attached above ground to a center pivot sprinkler — in western Kansas.

“We found that about a 35% reduction in soil surface evaporation can be achieved during the early stages of a crop,” he said. “But adoption by farmers is so far slow due to such factors as overall system management, cost and modified cropping practices.”

Still, Aguilar believes researchers are on the right track.

“Since the limiting factor in western Kansas is water, improving soil health will be key to capitalizing on the precipitation that dryland farmers can rely on,” Aguilar said. “Through research, we’ve found that crop rotation, insect and weed management, crop variety selection and better cropping practices will be key in helping transitioning dryland farmers to be economically competitive.”

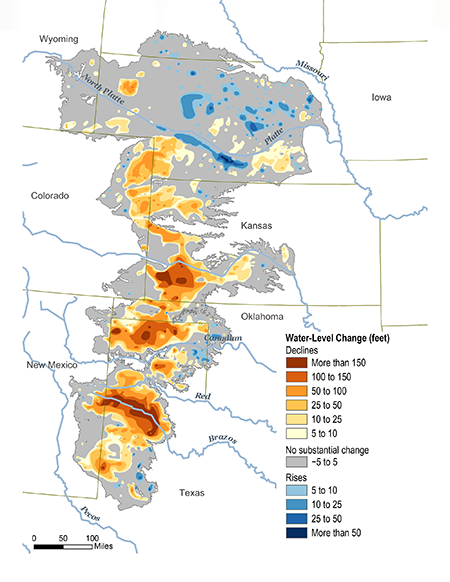

Managing the Ogallala Aquifer

No discussion of Kansas water and agriculture is complete without talking about the mighty Ogallala Aquifer, a shallow water table aquifer that stretches across 174,000 square miles and touches parts of eight states, including the western third of Kansas. The Ogallala Aquifer is part of the High Plains Aquifer, which includes the Great Bend Prairie and Equus Beds aquifers in south central Kansas.

No discussion of Kansas water and agriculture is complete without talking about the mighty Ogallala Aquifer, a shallow water table aquifer that stretches across 174,000 square miles and touches parts of eight states, including the western third of Kansas. The Ogallala Aquifer is part of the High Plains Aquifer, which includes the Great Bend Prairie and Equus Beds aquifers in south central Kansas.

The Ogallala Aquifer provides far more water for Kansas croplands than any other aquifer in the state. Various sources indicate that 80% to 95% of groundwater pumped from the Ogallala Aquifer goes to irrigated agriculture.

The problem is that the Ogallala Aquifer is not an infinite resource, and the rate at which water has been taken out over 100 years has far exceeded the rate at which the aquifer has recharged itself.

“Given the depth to water, groundwater usage and the semi-arid climate, the Ogallala tends to be in a state of decline,” said Brownie Wilson, a GIS/Support Services manager with the Kansas Geological Survey’s geohydrology section.

K-State, West Texas A&M University and Texas A&M University formed the Ogallala Aquifer Program, or OAP, in 2003 to develop a long-term approach to quickly address emerging research questions related to the aquifer. Funded by the USDA, the OAP competitively funds one or two years of research for immediate projects related to the Ogallala Aquifer, Metzger said.

“Projects have ranged from soil health practices to economic questions such as what the boom in the dairy industry is going to do to the value of water in the state,” Metzger said. “Literally hundreds of questions have been answered within one to two years from when they were first posed. These are rigorous research projects because of the OAP partnership.”

In early 2022, K-State agricultural economists Gabe Sampson, associate professor, and Nathan Hendricks, professor, reported study findings that land values in the Ogallala Aquifer region are $3.8 billion greater today than they would be without access to the aquifer, largely because of crop production on that land. But they also studied cattle production and found that access to the aquifer increased animal sales by $2.4 million annually in Kansas and increased the number of cattle on feed by 2.4 million head.

So how much water is left in the aquifer? Wilson said it’s hard to know exactly, but the Kansas Geological Survey draws its estimates on the Ogallala Aquifer’s life by assuming a minimum flow rate of 200 gallons per minute over the course of the summer.

“With that metric, the lifetime answer varies by location and is driven by how much water is in the ground currently, how much is used each year and what the rates of decline are,” Wilson said. “Some areas of the aquifer have 25 years or less until they’re depleted; some have 100 years or more.

“Some are there already.”

Getting back to business

Dry grassland is only one factor that has contributed to wildfires in parts of Kansas in recent years. Mark Neely, the state fire management officer for the Kansas Forest Service, said some of the effective barriers against fire include grass strips mowed in different vertical arrangements; plowed or disked rows; moist bottom woodlands; and prescribed burns that reduce woody encroachments.

“A lack of prescribed fire on rangeland allows woody species to encroach, especially eastern red cedar, which provides a high fuel load that releases more energy and is harder to suppress,” Neely said.

“A lack of prescribed fire on rangeland allows woody species to encroach, especially eastern red cedar, which provides a high fuel load that releases more energy and is harder to suppress,” Neely said.

Neely said the Kansas Forest Service, an independent agency in K-State Research and Extension, has fire personnel in six Kansas fire districts and provides assistance to local fire authorities. He said the agency typically responds to 20-30 fires per year, though fire incidents “have gotten bigger and more destructive.”

“In the past, a volunteer fire department may respond to a fire and be done in two to four hours,” he said. “Now, fires are lasting days, which is stressing the volunteer service and their employers.”

Since the 2017 Starbuck Fire, the Gardiner family has mostly rebuilt operations to pre-fire existence. Gardiner lauded K-State Research and Extension’s help, as well as support and guidance from such state organizations as the Kansas Livestock Association and the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association.

In fact, he added, Gardiner Angus Ranch may be stronger today because of the tough times.

“This event also restored my faith in mankind,” Gardiner said. “The outpouring of support from so many will never be forgotten. We ‘get’ to live this great life and business. My father, Henry Gardiner, always said, ‘We can do this … so let’s get to doing.’”