A solid defense: Research tackles military challenges from every angle

By Megan Saunders

Kansas State University research can be found in military operations and hospitals, in cybersecurity technology and in communities overseas.

University researchers are playing a key role in securing our nation, particularly through partnerships with the U.S. Department of Defense and related entities. The university has more than 75 DOD-funded grants totaling nearly $20 million from fiscal years 2015-2019.

Each grant funds research that will affect our nation and its military personnel for years to come. Read on for a sampling that highlights university DOD-funded projects that span disciplines, time and personal connections.

These walls don't talk

Robby and John Hatcliff, computer science

DARPA grant

Connectivity is crucial to military operations, but with increased connectivity comes potential high-stakes security hazards.

Robby, professor of computer science, and John Hatcliff, university distinguished professor of computer science, are part of an international team that is developing cyber-resilient embedded systems. The team is using a Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, grant to turn architectural models of these systems into an executable, real-world cybersecurity approach for military-crucial equipment, such as an unmanned aerial vehicle, or UAV.

“If a UAV in flight is communicating with a source on the ground, you want to ensure you’re communicating that information to the right source,” Robby said.

Data61, the digital innovation arm of Australia’s national science agency, is providing a framework for building system architectures with security properties that have been mathematically verified using computer-checked proofs. Meanwhile, researchers like Robby and Hatcliff are translating architectural models into the code level to run on Data61’s framework in the real world.

“In some sense, it’s like building a house where you use architecture to build very strong walls so you can only get from one room to another through a controlled mechanism,” Hatcliff said. “When you’re certain that the transition from a particular door is being closely controlled, you don’t have to worry about someone making a hole in the wall, like a hacker trying to introduce malware.”

Security is never completely guaranteed, especially in a software-oriented world prone to intrusion. That’s why the DARPA team also is focused on cyber resiliency. The researchers are determining highly critical system pieces and isolating them from other, less-crucial segments, which enables the system to still function even when some pieces are compromised.

“Since they’re walled off, if someone breaks into a particular room, the system allows you to isolate and lock that door, preventing others from getting through,” Hatcliff said. “You’re resilient to attacks and able to fight through them. Even though there may be a security breach, you can still make progress toward accomplishing your mission.”

Another issue that frequently exists in military cyber systems is difficulty in creating change. Often, a component is intertwined with the rest of the system, which makes it difficult to make an update without upending the entire system. Robby said by focusing on the system architecture, it becomes possible to change something in a single partition.

“Since you know you’ve been careful about how that system communicates, you have confidence that it’s not going to impact the rest of the system in unanticipated ways,” he said. “It’s a much better approach for updates to system components.”

For example, since unmanned aerial vehicles are used in many types of missions, including low-ground work and night missions, it is necessary to constantly reconfigure them for mission objectives. The framework Robby and Hatcliff’s team is developing makes it much easier to know the cyber system will work correctly when needed.

The K-State researchers’ collaborators on the $800,000 DARPA project include Data61; Adventium Labs in Minneapolis; Collins Aerospace in Cedar Rapids, Iowa; and the University of Kansas.

Improving relations

Michael Flynn and Carla Martinez Machain, political science

Minerva Research Initiative grant

U.S. military service members work throughout the world in small numbers and large deployments, on battle frontlines and in humanitarian work. Regardless of assignment, this work is essential, yet two K-State researchers and their team are concerned that little is known about the effects these deployments may have on their environments.

Michael Flynn and Carla Martinez Machain, both associate professors of political science, are using a $1.2 million U.S. Department of Defense Minerva Research Initiative grant to study the long-term effects of overseas deployments on attitudes toward the U.S. This includes not only general perceptions, but also crime statistics and local economic impact.

“In past decades, we saw a lot of information from more of an editorial, anecdotal standpoint,” Flynn said. “Instead of drawing from these isolated cases, we’re studying perception and how it manifests itself in different, measured ways, including how opinions about the U.S. military extend to the general U.S. population and government.”

The grant has allowed Flynn and Martinez Machain to carry out online surveys as well as visit six countries — Panama, Peru, England, Germany, Japan and South Korea — to interview U.S. and host country military, civilians and government officials. Altogether, their surveys have reached 14 countries in noncombat zones, most with at least 1,000 U.S. military personnel deployed annually. The researchers have made some exceptions for countries such as Poland that have smaller U.S. deployments with political importance.

Although the researchers’ main focus is countries with a long-term U.S. presence — such as Germany, Italy and South Korea — they also have interviewed people in Latin American countries, including Panama and Peru, for their smaller humanitarian civic assistance missions.

“We took a mixed-method approach, utilizing hard data and statistical analysis alongside field work,” MartinezMachain said. “We surveyed different social classes and interviewed local government officials, U.S. diplomatic and military officials stationed abroad, and journalists to find out how their perceptions are formed.”

The researchers already have gathered large data subsets that give a glimpse inside deep-rooted perceptions of the U.S. They have found that perceptions are influenced by the amount of indirect or direct contact with U.S. troops, how aid is attributed by the U.S., the degree of threat by outside powers, the length of the U.S. deployment and other nuanced opinions.

The researchers plan to repeat the survey twice more in each country to explore evolving patterns. The next project phase will focus on the military’s economic footprint in these countries as well as crime data.

“The military is embedded in a broader social, economic and political system,” Martinez Machain said. “It isn’t until you analyze these issues in a socially scientific way that these answers become clear.”

From a policymaking perspective, Flynn said they want to simply provide lawmakers and military officials with tools to make informed decisions and with sound guidance for leaving a particular impact on a foreign nation.

A new handle on healing

Sherry Fleming, biology

Department of Defense grant

Jerald, an 80-year-old Vietnam War veteran medic, inspired Sherry Fleming’s research years ago while she was completing her postdoctoral work at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Maryland.

“He told me about these badly injured soldiers they would treat and get ready to send home,” said Fleming, professor of biology. “Then, several days later, they would crash for seemingly no reason. Today, we know that post-trauma inflammation was most likely responsible. I explained that to Jerald and all he said was, ‘Well, what are you going to do about it?’”

Fleming has since searched for the answer by investigating differences in post-trauma medical treatment for men and women. She recently received a $650,000 U.S. Department of Defense grant to research how male and female hormones cause different physical reactions to post-traumatic injury treatment. Trauma causes bleeding — damage from the actual wound — as well as trauma-related inflammation from the body’s immune system, Fleming said.

“Your immune system protects you, but it also can overreact and cause additional damage as it is healing you,” she said.

For example, if an individual has a heart attack caused by a clogged artery, cells won’t receive blood flow and will die. But when doctors open the artery and allow blood to flow through, the immune response can cause further damage.

“It’s allowing your heart to recover, but the inflammation can cause even more damage,” Fleming said. “That’s what we want to stop.”

Men and women often have different symptoms when suffering a heart attack, and Fleming is investigating if hormonal differences may be to blame. If so, these hormones also could affect how the body reacts to trauma.

“Preliminary data suggests this may be the case,” Fleming said. “Female soldiers who are hit by an improvised explosive device and receive treatment similar to their male counterparts are dying at a much higher rate than men.”

In fact, one study suggested that the death rate for injured female soldiers was almost twice as high. Fleming’s research is aimed in two potential directions. First, some data suggests the body reacts differently because of the lack of testosterone, as opposed to the presence of estrogen.

The second approach is related to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or NSAIDs, which stop the swelling that starts in one molecule before becoming prostaglandins, which are hormonelike chemical compounds. Preliminary data suggests that men may make larger quantities of prostaglandins than women after a traumatic incident.

“We may simply be making different amounts of soluble molecules,” Fleming said. “If that’s the case, we may already have the drugs necessary for treatment.”

Fleming’s team holds a drug patent that could prevent antibodies in blood from binding and causing further cell damage.

“It’s amazing what sort of trauma we can live through, only to turn around and have your own body cause this extra damage,” Fleming said. “Soldiers are dying because we don’t understand what’s going on. These men and women are important to me, and if I can do something to help them, then that’s important, too.”

The light of day

Nick Wallace, biology

Career Development Award

Every year, 3 million cases of skin cancer are diagnosed in the U.S. and $4.8 billion is spent treating these patients, according to the Skin Cancer Foundation. Skin cancer is especially common among active military members and veterans, often because of the extreme sun exposure in the locations of their deployments.

Nick Wallace, assistant professor of biology, is using a $510,000 Career Development Award from the U.S. Department of Defense Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs to research an unexpected link between skin cancer and sun exposure: human papillomavirus, or HPV.

“Nearly 80 percent of people contract some form of HPV in their lifetimes,” Wallace said. “We know sexually transmitted HPV can cause cervical cancer, but the DOD wants to know if skin-to-skin HPV infections combined with sun damage also may cause skin cancer.”

Although the military has made a lot of progress in ultraviolet, or UV, radiation prevention, little is known about whether a viral infection may make sun damage even worse, Wallace said. Researchers recently have discovered strong links between several forms of skin-to-skin HPV, UV damage and skin cancer.

If Wallace can provide solid evidence that these interactions are taking place, it’s a relatively simple fix to adjust the current HPV vaccine to include skin cancer protection. HPV protection also could be included as a sunscreen additive.

“During sun exposure, the HPV binds to a protein that affects the cell’s response,” Wallace said. “If we can block the virus’ interaction with that cellular protein through an additive, we could target soldiers or civilians at a critical moment as they apply sunscreen before direct exposure.”

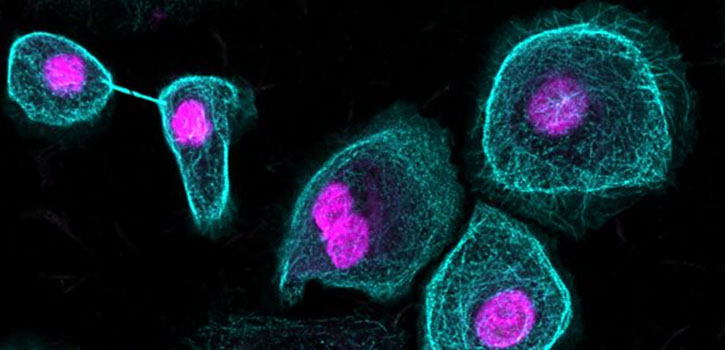

Wallace’s lab work includes taking normal skin cell samples, adding HPV proteins to a select number and exposing them to UV and other damaging agents.

“Cells are constantly dividing, and about 10 percent of the time they can make a mistake,” Wallace said. “This can double the amount of DNA, which can be worsened by UV and put cells at risk for developing cancer.”

Wallace is taking pictures of these cells with fluorescent markers to determine their response to UV damage. Looking closely at individual cell proteins, he studies how these infections change skin cells.

Both at home and internationally, Wallace said the response to his team’s work has been incredibly rewarding.

“We don’t want our discoveries to sit on a shelf, but we want to unveil them so people can ask even more questions,” Wallace said. “Community engagement means a lot, particularly when it comes to protecting our nation’s soldiers.”