Dog's best friend: Humans are fetching up new ideas to improve health of canine companions

By Stephanie Jacques

A dog's smile — that drooling, bad-breath smile — warms a dog lover’s heart and begs for a pat on the head or a scratch behind the ears.

Kansas State University researchers and veterinarians are giving that and more to improve health for man and his best friend.

College of Veterinary Medicine researchers are extending pets’ quality of life while learning more about diseases that cross the species border between animals and people, such as breast cancer, bone cancer and arthritis.

“Similarly to how diseases in animals have been studied to advance human health, what we know about human diseases also can be applied to animal health,” said Denver Marlow, university veterinarian and director of K-State’s Comparative Medicine Group. “There are many noninfectious, naturally occurring diseases that affect both animals and humans.”

According to researchers in the College of Veterinary Medicine, understanding and treating dogs with naturally acquired diseases can provide insight into human diseases since dogs have cellular similarities to humans, often share human environments and can share diseases.

“It all goes back to One Health,” Marlow said. “What we learn about animal health helps advance veterinary and human medicine, as well as the discovery of new vaccines, drugs or therapies for treating or preventing diseases in animals and humans.”

The One Health concept that human health is linked to animal and environmental health encourages collaboration among human health professionals, veterinarians and scientists on various stages of research — basic research in a lab, model systems testing, safety testing and, finally, clinical trials.

Among those working on health-related research in the college are three researchers who are at various research stages and who are specifically investigating diseases that affect dogs and humans.

Deciphering canine cellular communication

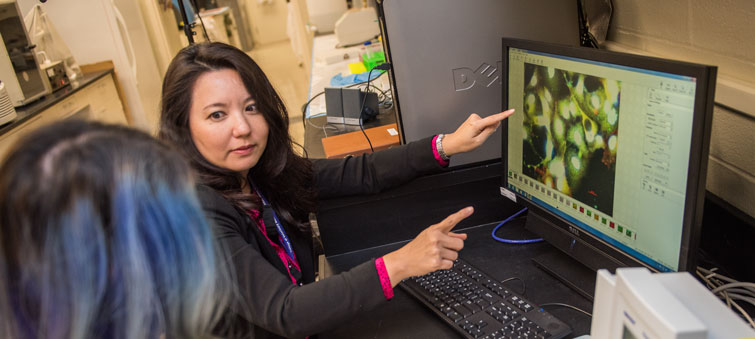

| Annelise Nguyen, associate professor in diagnostic medicine and pathobiology, discusses canine mammary carcinoma cells with Savannah, Luu, a second year veterinary medicine student. |

Understanding the secret language of dogs is more complex than figuring out what woof, bark and bow-wow mean. Annelise Nguyen, associate professor of diagnostic medicine and pathobiology, is looking deeper at canine cancer cell communication — or lack thereof. The research is based on her previous work with human breast cancer.

“There is a lack of understanding of cell-to-cell communication,” Nguyen said. “Normal cells have great communication and regulation. "We do not see that with cancer cells. We want to learn more about how the loss of cell communication is the driving force of cancer.”

According to Nguyen, current cancer treatments in dogs kill all cell growth — harming even healthy cells — in order to prevent the cancer cells from growing.

Nguyen is looking for a more targeted approach that could open up closed communication channels called gap junctions in cancer cells and allow proteins that regulate cell growth back into the cell.

The approach already has been successful in Nguyen’s human breast cancer research and resulted in a patent.

“If the cell communication blockage is there in humans, it could be in dogs, too,” Nguyen said. “If we can show that is the case, it would be the first research to demonstrate this pathway occurs in canine carcinoma.”

Nguyen and Savannah Luu, second-year veterinary medicine student, spent summer 2016 researching if cancer cells in dogs have the same communication barrier. They tested three cell lines of canine mammary carcinoma — the dog version of breast cancer and the most common cancer in unspayed female dogs. In the in vitro tests, Luu found a decrease in the connexin 43 protein of the CMT27 cell lineage, which she said might be the cause of the loss of cell communication and has potential for targeted therapeutics that are needed in veterinary medicine.

“As a veterinary student working in clinics, I’ve seen several dogs get cancer — nearly every one above the age of 10 — so I wanted to make a change,” Luu said.

Nguyen and Luu said the targeted approach could prolong dogs’ quality of life and give a comparison to what the therapy can do for humans.

“If a dog gets cancer at 10 years of age, we can’t prevent death but we can prolong their quality of life,” Nguyen said. “This is an approach, a treatment, that could add two to three years — that’s worth it. In dog time, that’s a long time. In humans, a comparable time frame would give more time to a patient for personalized care.”

Give a dog a bone-fighting chance

| Realene Wouda, assistant professor of clinical sciences, administers a small dose of chemotherapy to Abby, a 7-year-old Saint Bernard mix with cancer. According to Wouda, the small dose extends the patient's quality of life and prevents sickness. |

Built into a veterinarian’s DNA is a love for animals and a desire to improve their health and welfare. Raelene Wouda, assistant professor of clinical sciences, is such a soul who is trying new treatment approaches to give her patients and their owners hope.

Wouda and her colleague Mary Lynn Higginbotham, associate professor of clinical sciences, oversee an active clinical trials program at K-State’s Veterinary Health Center. One of their current clinical trials is enrolling pet dogs diagnosed with osteosarcoma, the most common type of primary bone cancer in dogs and people, particularly children and young adults.

“Clinically and genetically, osteosarcoma is indistinguishable between dogs and humans,” Wouda said. “Any treatment we develop that shows clinical benefit in our canine patients can therefore be translated to provide benefit for children with osteosarcoma.”

The osteosarcoma clinical trial at K-State is part of a multi-institutional trial overseen by the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute’s Comparative Cancer Research Center and its comparative oncology program.

Nationwide, the clinical trial has now enrolled more than 150 of the 200 desired canine participants to research the therapeutic role of rapamycin, a molecularly targeted drug that modifies the patient’s immune system.

Preliminary research suggests that rapamycin might inhibit the spread of disease to the lungs, which is common in the late stages of osteosarcoma.

“Many of our clinical trials at K-State’s Veterinary Health Center are predicated on ideas gleaned from human medicine, and we try to use those in our veterinary patients and vice versa,” Wouda said. “Information we develop can certainly be translated into human oncology and other areas of medical research. If the canine osteosarcoma trial is successful, this treatment will move onto trials in human pediatric patients.”

All the pet dogs enrolled by their owners in the study receive the standard-of-care treatment, which involves amputation of the cancerous limb followed by carboplatin chemotherapy. Wouda said the average survival time for dogs with osteosarcoma that undergo only an amputation is approximately four months. With the addition of chemotherapy, the average survival time is closer to 10-12 months. After the standard-of-care treatment, half of the enrolled dogs are randomized to receive rapamycin for several months. The clinicians then follow the dogs, specifically mapping their disease-free periods and comparing between the two groups.

“We hope that by adding rapamycin to a patient’s treatment plan, we are providing an additional way to kill or inhibit the tumor cells in the dogs and improve their survival time, or even achieve a cure in a certain population of patients,” Wouda said.

According to Wouda, a growing number of pet owners are seeking high-level medical care for their pets. They might choose to participate in clinical trials for a variety of reasons, including access to novel therapeutics.

Clinical trials are especially attractive to owners whose pets have not responded to standard-of-care therapy or for those that the existing therapies do not achieve ideal outcomes, she said. The willingness increases the chances of success for comparative studies like the osteosarcoma trial that will benefit both canine and human health.

“Our pet dogs live longer now than they used to because of a combination of improved veterinary care and improved client care,” Wouda said. “Consequently, we have the opportunity to answer critical research questions in a timely manner using a population of dogs with comparable diseases, shared environmental circumstances, access to high-level health care, and comparatively shorter lifespans — one dog year equals seven human years. These factors and wonderful owners who are willing to pursue investigational therapies provide a steppingstone for improving the outcomes of both pets and humans with cancer.”

Arthritis relief stems from cells

| A pressure-sensing walkway provides objective sata of a dog's pain severity by measuring how much weight the dog puts on each foot — a first in canine stem cell studies. |

Mark Weiss, professor of anatomy and physiology, has unbiased data to change the game of fetch for dogs with inflammatory diseases.

Weiss has finished a clinical trial that used stem cells in dogs to decrease pain from osteoarthritis, also a disease that affects humans. The study showed objective data — a first in canine studies with stem cells — that the therapy is effective at reducing pain.

“The preclinical data suggests that stem cell therapy could be disease-modifying — a game changer,” Weiss said. “We wanted to see if we could make clinical improvements in the animals. That’s what we got.”

The study, which enrolled 22 dogs diagnosed with hip arthritis, followed the patients for six months after placebo or stem cell therapy. The study was a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, which means the veterinarian and the dog owner did not know which dogs received the stem cell treatment and which received a placebo injection.

“There is a placebo effect, even in dogs,” Weiss said. “Part of the problem is that dogs are not the ones telling you they feel better. Dogs attempt to please their owners, and if owners are biased and expect to see an improvement in their dogs, then there is a placebo effect in the short term.”

The computer measurements from a pressure-sensing walkway showed that dogs that received stem cells — collected from the dogs’ intestinal fat — had moderate improvements in weight distribution within the first month after the injection. The walkway provided measurable data in addition to subjective data from owner and veterinarian surveys that indicated that the dogs that received the treatments had significant functional improvements.

“We had baseline, one-month, two-month, three-month and six-month measurements from the walkway after treatment,” Weiss said. “At one month, the treated dogs had shown improvement and they remained improved six months later.

We are extremely excited that our study showed that stem cells were safe and had a positive effect.”

Weiss is recalling the dogs involved in the study to make a case to start a similar clinical trial in humans with arthritis.

“The potential of these findings to inform and translate human medicine is huge,” Weiss said. “If we can safely and effectively treat dogs with arthritis, then we can make a case to use stem cells for treating humans with inflammatory diseases.”

Read the rest of Seek and see the PDF version of this story from New Prairie Press.