Meeting the moment

The Carl R. Ice College of Engineering is developing the next generation of nuclear engineers

he next time you plug in your phone, ride in an electric car or make a web search driven by artificial intelligence, think about the energy required to make that moment possible. From data centers running around the clock to banks of electric car chargers, the world’s appetite for energy is soaring faster than ever.

Meeting that demand is one of today’s defining challenges, and as the U.S. looks at alternative, sustainable energy sources, nuclear power is quickly emerging as a key component of any solution. New plants are breaking ground around the country, and a new generation of nuclear engineers will be in demand to design, build and operate these reactors.

Kansas State University is cultivating that next-generation workforce as it leverages its TRIGA Mark II nuclear reactor facility — one of only 25 university-operated research reactors in the country — to equip students with the skills and hands-on experience needed to power America’s future.

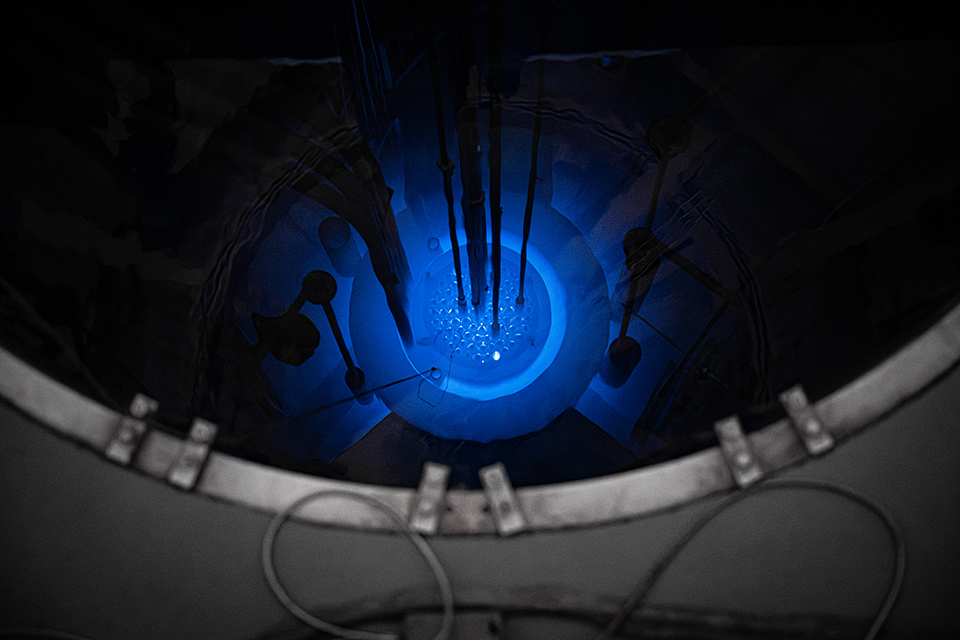

Above: The core of K-State's TRIGA Mark II nuclear reactor.

“The nuclear industry has long been an important component of the nation’s energy landscape,” said Amir Bahadori, nuclear engineering program director and professor of mechanical and nuclear engineering in the Carl R. Ice College of Engineering. “But things seem to be accelerating now. It’s really having a moment.”

And beyond energy production training, K-State’s nuclear reactor is powering impactful research, developing innovative materials and methods that will help answer society’s pressing questions in fields from healthcare to agriculture to manufacturing.

With interdisciplinary applications beyond nuclear engineering, the reactor is a key component of the university’s role in analyzing and developing new materials, processes and technologies, said Alan Cebula, reactor manager.

“K-State’s reactor supports research that directly affects the state,” Cebula said. “Our reactor is set up well to be flexible to meet the needs of researchers and their experiments, and we can also develop new capabilities as needed.”

During operator license training, Ethan Ross, senior in mechanical engineering with a nuclear engineering option, observes and records reactor parameters as Amir Bahadori discusses the reactor instrumentation and control systems.

The core of discovery

Designed for nuclear research and education, K-State’s TRIGA Mark II reactor is licensed to operate at up to 1.25 megawatts of thermal power — putting it among a handful of university research reactors that can generate more than 1 megawatt.

For comparison, the Wolf Creek Nuclear Generating Station in eastern Kansas generates approximately 3,600 megawatts, or nearly 3,000 times as much thermal power, although K-State’s reactor does not generate electricity.

The TRIGA Mark II reactor uses a swimming pool reactor design, meaning the reactor core — itself surrounded by a graphite reflector — is submerged in a water-filled tank. This large, tub-like pool of water, surrounded by a radiation shield, acts as a cooling agent. Throughout the entire reactor area, different spaces between these barriers allow for research using varying levels of radiation.

The reactor’s fuel is specially designed to inherently control power increases as the core’s temperature increases, meaning it is essentially impossible for the reactor to melt down, Bahadori said.

As with any laboratory space, students and researchers who utilize the TRIGA Mark II nuclear reactor must learn to do so safely. Anyone inside the reactor room in Ward Hall must closely coordinate with reactor operators beforehand and wear a dosimeter to measure any potential radiation exposure as part of the facility’s standard safety protocol.

K-State’s reactor operations team has performed regular inspections and maintenance to keep the reactor in safe operating condition since starting operations.

For example, a recent period of downtime for maintenance allowed the team to clean the reactor’s fuel using a specialty contractor-designed ultrasonic tool. Reactor staff also used the downtime to upgrade other components and ensure the restored reactor would be fully up to standard.

“It’s a safe tool we use for experiments and for teaching,” Cebula said. “We get students that hands-on, applied learning experience.”

Carter Comer, sophomore dual majoring in mechanical engineering and nuclear engineering, tests the safety functions of a new reactor control console for replacing existing instrumentation.

Bringing back the bachelor’s

The Carl R. Ice College of Engineering welcomed undergraduate students majoring in nuclear engineering back to campus this fall for the first time in nearly 30 years.

Armed with the institutional advantage of an on-campus reactor once again in full operation, the program aims to prepare the next generation of nuclear engineers for a career in an increasingly high-demand field.

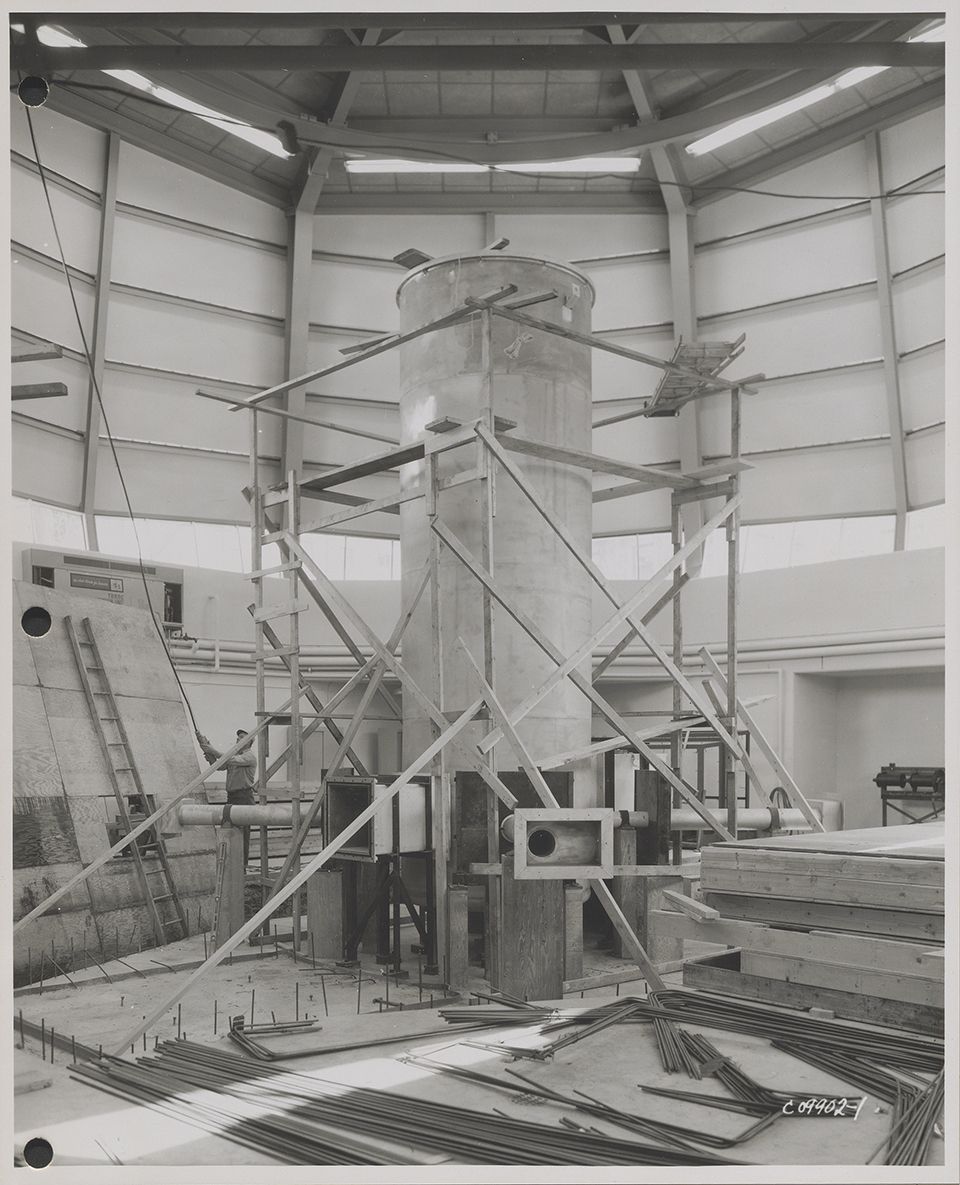

Built in the early 1960s, K-State's TRIGA Mark II reactor first achieved criticality at 8:27 p.m. Nov. 16, 1962.

The nuclear engineering bachelor’s degree, approved by the Kansas Board of Regents over the summer and offered through the Alan Levin Department of Mechanical and Nuclear Engineering, will prepare its graduates for a world that continues to need more nuclear engineers.

Bahadori said these engineers will design and improve reliable, efficient nuclear energy generation, develop life-saving innovations in medical imaging, treatments and therapies, and contribute to national security through the advancement of nuclear safety, radiation protection and defense technology.

But it’s not just traditional college students who will benefit from this new degree. Bahadori sees K-State as uniquely positioned to leverage the TRIGA Mark II nuclear reactor facility to connect with industry partners in new ways as the demand for nuclear-capable and properly licensed operators continues to surge amidst plans to bring new reactors online across the country in the coming months and years.

“We’ve had discussions with companies that want to use the reactor as a resource to help educate their employees, giving them hands-on experience that they haven’t had in their engineering career,” Bahadori said. “Or there are some that need an initial introduction into nuclear, given the fact that there’s this huge workforce increase required to expand nuclear power to meet our energy needs.”

Kael Schwabauer, left, junior in nuclear engineering, and Danny Eckerberg, master’s student in nuclear engineering, prepare a sample for irradiation in the reactor to conduct a Neutron Activation Analysis experiment.

Nimble but powerful

As a strong source of neutrons, the reactor offers a variety of research opportunities for faculty across the university as well as externally, said Cebula, the reactor manager.

Much like other spaces on campus, the reactor is available to use as a fee-based lab space for anyone wanting to conduct specific research. With various experimental facilities in and around the core, researchers have access to different radiation exposure scenarios.

One use the reactor has seen growing interest in is generating small-batch medical isotopes — neutron-activated therapeutic isotopes and radiotracers that help doctors understand how human and animal bodies function —for medical research. By exploring these isotopes, researchers can better diagnose, treat and research human and animal diseases.

Reactor manager Alan Cebula walks a class of nuclear engineering students through the various procedures needed to conduct a reactor pulse.

Using neutron radiography and tomography, as well as neutron activation and analysis, the reactor also provides researchers with the ability to examine materials and prototypes at an ultra-precise level.

For example, the reactor’s capabilities could find tiny, microscopic fractures on the inside of a turbine blade that would be impossible to find otherwise, or they could find trace amounts of heavy metals — at a level of parts per billion — in samples of drinking water.

“Where an X-ray might not be able to see past a certain kind of material, a neutron, with its neutral charge, can see inside an object that’s been manufactured without destroying that object to look for manufacturing defects and make sure it’s up to specification,” Cebula said.

Research and radiation

For Bahadori specifically, access to the reactor allows him to move forward with partnerships with other K-State faculty, including Shih-Kang “Scott” Fan, professor of mechanical and nuclear engineering, and Brad Behnke, professor and Betty L. Tointon Dean of the College of Health and Human Sciences.

That work centers on integrating three main areas of radiation research: radiation biology, radiation dosimetry and radiation epidemiology.

The project takes a more holistic view of how radiation affects entire organisms, as opposed to much of the current research that examines the effects of exposure on specific cells or organs.

“We want to use the information that we can gather from radiation biology to inform epidemiological models and try to identify key events that happen after the original radiation exposure,” he said. “We will link these events to the ultimate outcome, like cancer, which is the radiation health effect that people usually think about. That’s a really complex process.”

“The nuclear industry has long been an important component of the nation's energy landscape. But things seem to be accelerating now. It’s really having a moment.”

The research has the potential to help mitigate the chronic radiation risk that accompanies a variety of careers, including pilots and other aircrew who spend time at high altitudes, astronauts embarking on missions to Mars, doctors and radiation technologists who operate radiation-emitting medical devices, as well as those working in the nuclear energy or defense sectors.

By determining the key points between a person’s exposure to radiation and clinical disease development, Bahadori seeks to identify those who may be at most risk and implement methods that could better protect them.

“It really boils down to having the right estimates of radiation exposure, which is the dosimetry aspect, understanding biological mechanisms that result in radiation-induced disease, which is radiation biology, and having population studies that help us validate the models that are created through the radiation biology investigations,” Bahadori said.

“Using the reactor as a source of exposure is a very important part of that.”![]()

◊◊◊

Seek magazine

Seek is Kansas State University’s flagship research magazine and invites readers to “See” “K”-State’s research, scholarly and creative activities, and discoveries.