Protecting the plains

Inside the K-State lab safeguarding America’s food

mericans trust the safety and security of their food. Kansas State University plant pathologist Jim Stack says our trust is well-founded, pointing to a series of checks and balances that help to ensure that the food we eat arrives safely and on time at the dinner table.

Consider this: Farm crops — be they wheat, corn, soybeans, sorghum or many others — face daily challenges in the farmer’s field due to such threats as insects, diseases, weeds and weather events.

If the crop passes the test, it’s on to harvest with heavy machinery, then storage in bins and distribution through any of several channels — truck, ship, train and even airplane. Then there is processing and packaging the food, retail storage and marketing, and then it’s off to a kitchen where Americans have the ultimate responsibility to chill, clean and cook the product safely.

“Most of the foods in Kansas grocery stores were not grown in Kansas; they were produced elsewhere and transported into Kansas,” Stack said. “That is true for most U.S. states and many countries globally. Our foods are grown in multiple locations and transported to multiple locations. This creates the significant risk of transporting pests and pathogens with their foods and their containers.”

Because there are threats throughout the system, American agriculture must remain vigilant at every stage of food production.

Fortunately for American consumers, researchers at K-State and other universities are addressing many of these threats.

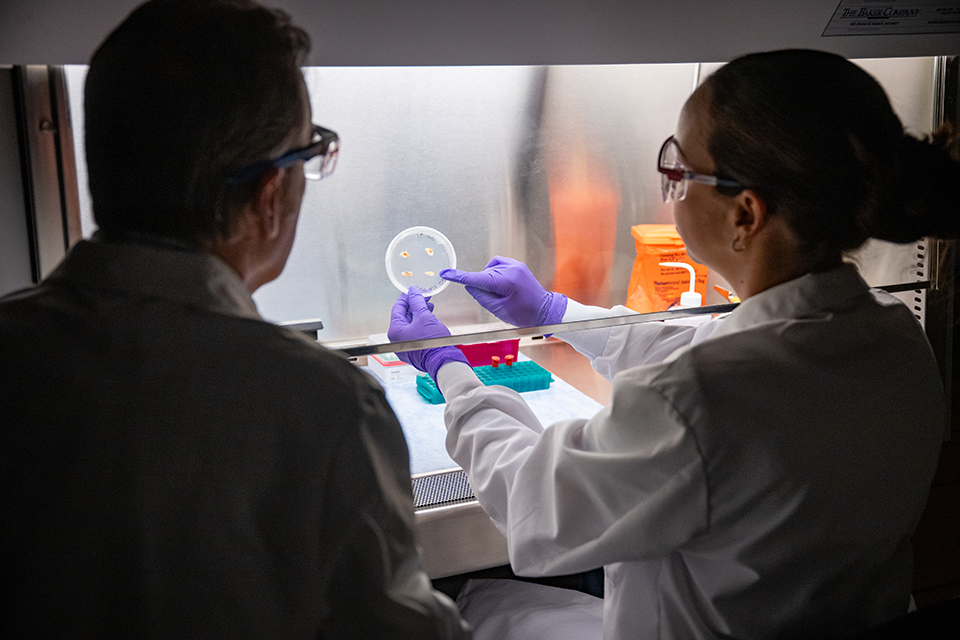

Giovana Cruppe and Jim Stack consult on a culture of plant pathogenic bacterium.

Plant experts dot the United States

Stack is the director of the Great Plains Diagnostic Network, one of five regional centers of the National Plant Diagnostic Network, established in 2002 by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and located on K-State’s Manhattan campus. The network was formed to enhance agricultural biosecurity by detecting potential disease outbreaks or bioterrorist threats.

K-State software engineers developed a lab management information system, called Plant Diagnostic Information Systems, that is used by many states nationwide. Today, the network has plant diagnosticians — including pathologists, entomologists, weed scientists and other plant specialists — who share information across the country to keep America’s food and fiber system as safe as possible.

“If countries want to participate in global trade, there is a set of rules that they must abide by,” Stack said. “Those rules are the basis of phytosanitary policy. The World Trade Organization designated the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization to be responsible for these rules, under the International Plant Protection Convention.”

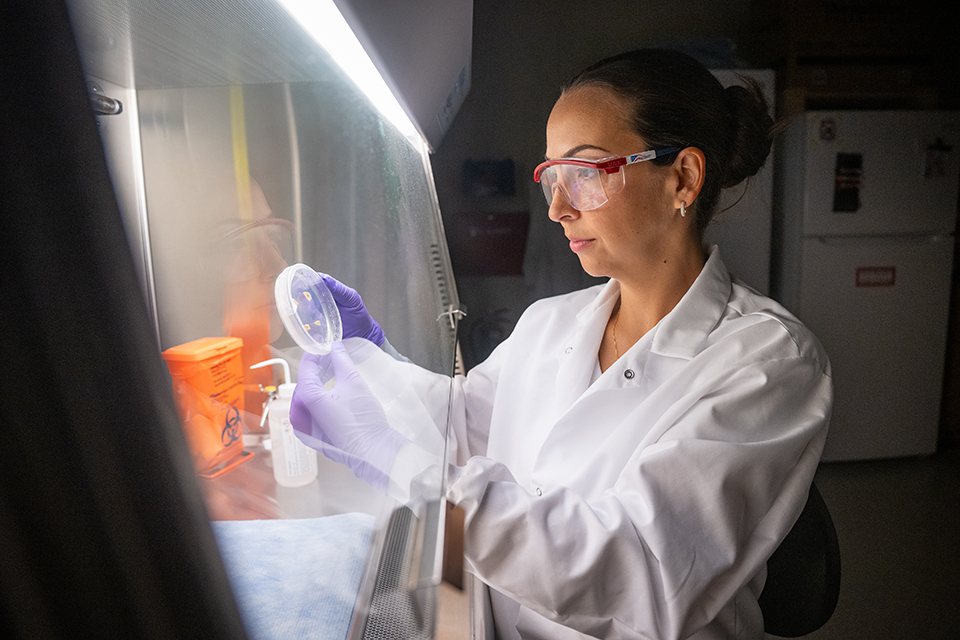

Giovana Cruppe, research assistant professor, examines a culture of a plant pathogenic bacterium in a biosafety cabinet to ensure containment.

The International Plant Protection Convention is a 1951 treaty between participating nations — the U.S. included — that aims to secure actions that prevent and control the introduction and spread of plant pests.

“Trading partners are required to put clean material into the global marketplace,” Stack said. "Some ways to determine if you’re doing that include incorporating best production practices, field surveillance and diagnostic testing.”

According to Stack, this process involves both identifying the organisim and understanding why the diseases or infestation is happening.

“We use a lot of technology to do that,” he said. “One of the positive results of having phytosanitary policies is that we’ve been cleaning up the plant material that is traded around the planet.”

No margin for error

Detecting plant pests and pathogens requires precision and accuracy, Stack said.

“Most international and federal response plans are linked to the name of the organism. If you don’t get the name right, you don’t have a legal right to respond to a suspected outbreak,” he said.

An incorrect diagnosis, in other words, might lead to the introduction, establishment and spread of a pest or pathogen.

“In 2010 in Australia, they discovered a new rust disease in a nursery in New South Wales that they called myrtle rust,” Stack said. “They quarantined the nursery to contain and eventually eradicate the pathogen.

Diagnostician Chandler Day performs triage determining needed diagnostic tests for a soybean sample submitted by a Kansas grower.

“But a secondary analysis indicated that it was not myrtle rust but rather guava rust; however, the response plan was for myrtle rust. While the discrepancy in the name was being resolved, the nursery was not precluded from trading its plants. While waiting to get a correct identification, the pathogen spread from New South Wales to Queensland and other places.”

The disease turned out to be myrtle rust after all, putting an estimated 70% of Australian flora at risk.

“That’s just one example,” Stack said. “There are multiple examples like that in countries around the world. We spend a lot of time and effort to get it right the first time.”

Fending off a destructive wheat disease

Samples of diseased and healthy wheat heads.

For decades, K-State scientists have had their eye on a particularly troubling disease capable of taking out entire wheat fields — wheat blast. Plant pathologist Barbara Valent initiated research projects at K-State that are considered the world’s most comprehensive studies on the disease.

Valent’s research team was the first to discover a source of resistance, called 2NS, for wheat blast. Her group also pioneered sophisticated microscopic techniques that allow them to watch and record how the disease develops cell-by-cell and hour-by-hour in amazing detail.

Prior to her retirement in late 2024, Valent had worked on understanding blast disease for more than 40 years. In 2022, she was recognized with membership into the National Academy of Sciences — the first scientist at K-State to earn the honor for original research conducted at the university.

The Biosecurity Research Institute, or BRI, is an enormously important part of K-State’s research infrastructure. Its biosafety level-3 labs have allowed scientists in the plant pathology department to develop the tools needed to prepare for a potential introduction of this pathogen into the U.S. and to identify effective sources of resistance to help mitigate the tremendous negative impacts of this disease.

“We are looking at the likelihood of detecting this pathogen by the methods that are commonly used in seed inspection,” Stack said. “And — I’ll just cut to the conclusion — it’s very, very unlikely to detect the pathogen that way. Unless it’s a full-blown epidemic, you’re probably not going to detect it.”

Protecting food security

“Our foods are grown in multiple locations and transported to multiple locations. This creates the significant risk of transporting pests and pathogens with their foods and their containers.”

The team of plant biosecurity scientists began developing different protocols to see if they could more accurately detect the presence of the wheat blast pathogen in a shipment of seed.

“We ended up with the conclusion that you could have up to 100 kilograms of infected seed in a 20-metric-ton harvest wagon, and you would not detect infected grain with traditional methods,” he said.

In other words, according to the researcher team, if even half of 1% of a shipment of seed goes undetected for wheat blast disease, that shipment could cause widespread devastation anywhere those seeds are planted.

“That seed is being shipped across the world, potentially into the United States,” Stack said. “If we’re not vigilant, we’re likely to experience more outbreaks.”

In addition to the continuation of Valent’s research, Stack’s lab studies bacteria and the emergence of new diseases that could potentially affect agricultural crops, like the corn stunt disease recently introduced in Kansas, as well as plant toxins that could be lethal to livestock if ingested.

Always on alert

The National Plant Diagnostic Network has provided diagnostic services to about 97% of the more than 3,000 counties in the United States since its inception 20 years ago, including territories in the Caribbean and Pacific.

“We span seven time zones and have about 75 active labs, plus partners in satellite labs. And the labs at the Department of Agriculture in some states are part of the network,” he said. “We also have a few industry labs that see value in this system.”

Stack said that the combined power of the network is critical because the consequences of a late detection or an inaccurate identification are quite serious for production and trade, not just domestically but also internationally.

“The result of disease introductions into our food systems is potentially the reduction of production, or at least lost potential,” Stack said. “You take a crop like wheat in Kansas — half of that is for export. Or think of corn and the diseases we are dealing with. About 80% of Kansas’ corn production is in southeast Kansas to support the livestock industry. If we can’t produce enough corn or produce it profitably, it will hurt both crop and livestock producers.”![]()

◊◊◊

Seek magazine

Seek is Kansas State University’s flagship research magazine and invites readers to “See” “K”-State’s research, scholarly and creative activities, and discoveries.