A new tick appears in Kansas, but fighting it is a familiar mission for K-State

Veterinary diagnosticians help producers stay informed as Kansas confirms live presence of Asian longhorned tick

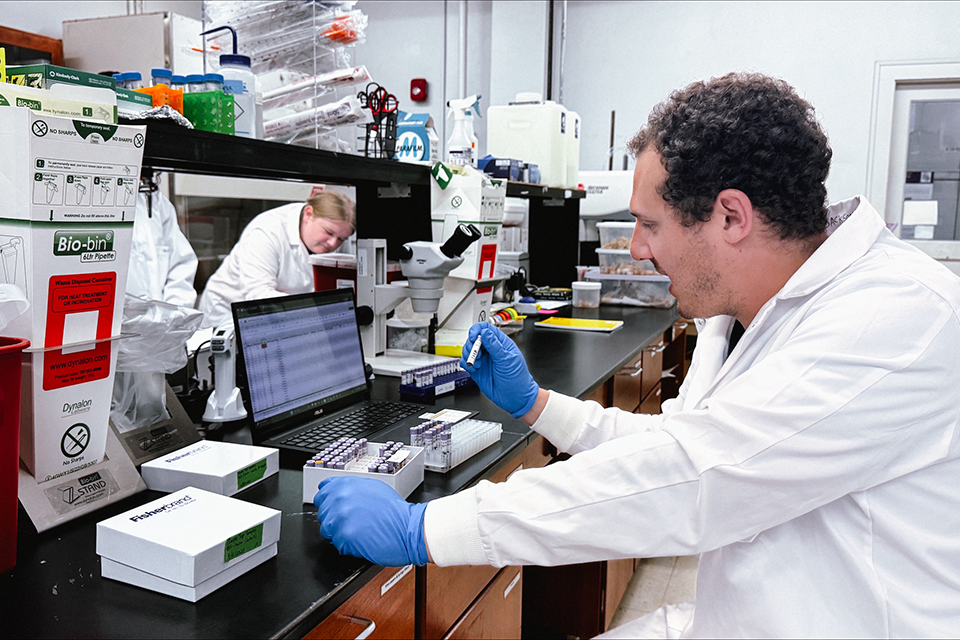

Researchers at the Kansas Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory are helping agricultural producers stay informed as Kansas confirms the first live detection of the Asian longhorned tick — an exotic, invasive species with cattle and human health implications. | Download this photo.

There's an emerging threat to Kansas cattle and human health, but one that experts at Kansas State University are prepared to monitor, diagnose and counter, as part of the university's mission to enhance biosecurity around the state and world.

Earlier in October, the Kansas Department of Agriculture confirmed the presence of a live Asian longhorned tick in Kansas — the first known detection of the exotic, invasive species in the state.

For Gregg Hanzlicek, professor and associate director of the Kansas Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, or KVDL, the discovery reinforced what K-State's veterinary medicine and extension programs were built to do: translate emerging science into practical tools for producers.

“This doesn’t mean we have a widespread or established population,” Hanzlicek said. “But it’s a reminder that these ticks, and the diseases they can carry, can move quickly. Awareness is key to limiting their impact.”

Understanding the risks of Asian longhorned tick Theileria orientalis Ikeda

The Asian longhorned tick is the primary vector for Theileria orientalis Ikeda, a protozoan parasite that infects red and white blood cells in cattle. The disease causes anemia, weakness and, in some cases, death. It is not responsive to antibiotics, and once infected, cattle remain carriers for life.

“It’s not a bacteria, it’s not a virus—it’s a protozoa that remains in the animal’s system for life,” Hanzlicek explained.

As the parasite invades and replicates in cattle red blood cells, it changes the surface proteins on each cell. The spleen identifies those cells as abnormal and removes them from circulation, which leads to anemia and deprives the animal of oxygen.

Affected cattle often appear weak, sluggish, and uncoordinated as their bodies struggle to function with reduced oxygen-carrying capacity.

While adult cows usually recover, young calves are far more vulnerable. In outbreaks documented in other regions, as many as 80% of calves became sick and nearly half died.

Late-term abortions have also been reported in some herds, though these cases have not been common in Kansas.

K-State researchers test cattle blood to check for disease that is vectored by the Asian longhorned tick from a neighboring state. | Download this photo.

KVDL is one of three US testing labs for Theileria orientalis

The Kansas Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory is one of only three laboratories in the U.S. with a validated polymerase chain reaction test to detect Theileria orientalis Ikeda.

Since 2022, the lab has tested about 2,000 samples from across the country, and roughly 38 percent have been positive — mostly from herds showing clinical signs of disease.

Housed within K-State's College of Veterinary Medicine, KVDL serves as the front line for animal health testing in Kansas and across the region. The laboratory conducts tens of thousands of diagnostic tests each year for veterinarians, producers, and animal health agencies—helping identify emerging diseases, confirm diagnoses, and protect both animal and public health.

“We have found one confirmed case — an older cow born and raised in Kansas that never left the herd and tested positive,” Hanzlicek said. “It tells us the tick is here, and we’re still learning as we go.

In addition to the tick, the longnosed cattle louse can also transmit the pathogen, and biting flies have also been proposed to be vectors, although both are probably likely less effective than the ticks.

Hanzlicek said diagnostic partnerships like this illustrate how Kansas State University fulfills its broader mission—translating science into action for Kansas agriculture. Through KVDL’s testing and consultation, veterinarians and producers can confirm suspicions quickly and take informed steps to protect herd health.

Testing is especially important in herds where cattle show signs of anemia, weakness or jaundice, or where unexplained calf losses have occurred.

“Our job is to provide answers,” Hanzlicek said. “The sooner we identify an infection, the better a producer can manage it and prevent further spread.”

How the Asian longhorned tick spreads

The Asian longhorned tick has a three-host life cycle, feeding on three different animals as it develops from larva to nymph to adult.

At each stage, it can acquire and transmit Theileria to new hosts.

“These ticks are amplifiers,” Hanzlicek said. “When they feed, their saliva contains high concentrations of the organism, and that’s how the infection spreads.”

Unlike most tick species, this one can reproduce with or without males, making it extremely efficient at establishing populations in new area. Every single Asian longhorned tick found outside its native range of central and east Asia has been female, and each one can lay thousands of eggs, allowing populations to grow rapidly once established.

The tick feeds on a variety of hosts — including cattle, deer, wildlife and birds — allowing it to move long distances. It has been documented in at least 20 states and continues to spread westward. The tick thrives in warm, humid areas, offering some hope that the drier regions of western Kansas may slow its expansion.

“We don’t believe it will survive in the drier regions of western Kansas,” Hanzlicek said, “but eastern Kansas could provide suitable habitat.”

Theileria diagnostic signs and transmission

Veterinarians often suspect Theileria when cattle show anemia or poor condition. Enlarged spleens are a common finding in necropsy exams.

“If we open up a case and see a very large spleen with a history of anemia, that gives us a pretty good idea what we’re dealing with,” Hanzlicek said.

There are currently no approved antimicrobial treatments for Theileria orientalis Ikeda in the United States.

Instead, management focuses on supportive care and prevention.

“Most animals will recover if they’re provided good husbandry — shade, bedding, clean water and proper nutrition,” he said. “Treatment doesn’t change the disease course, but management can make a big difference.”

He recommends regular tick inspections — especially around the ears, udder and tailhead — and the use of sprays, pour-ons or backrubbers for control. Ear tags alone are not effective.

Producers are also encouraged to isolate new or purchased cattle, particularly from regions where Theileria or the tick have been identified, and to submit any unusual ticks to KVDL or the Kansas Department of Agriculture for identification.

Keeping an eye for human health risks

While the Asian longhorned tick is primarily an animal health concern, it can also bite humans. In other parts of the world, the tick has transmitted diseases such as Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever.

“Right now, our concern is mainly for cattle,” Hanzlicek said. “But like any tick, people should take precautions: wear long sleeves, use insect repellent and check for ticks after being in grassy or wooded areas.”

The same vigilance that protects livestock, he added, also helps protect people.

Theileria orientalis Ikeda has been endemic in Asia, Australia and New Zealand for decades. In those regions, management focuses on reducing animal stress, improving nutrition and monitoring herd health rather than eradication.

“In Japan and New Zealand, they learned to live with it,” Hanzlicek said. “Producers focus on management and resilience. That’s likely what we’ll have to do here—stay aware, adapt, and make informed decisions.”

Gregg Hanzlicek presents on ticks and emerging cattle diseases at the K-State SREC Center's Beef Cattle and Forage Field Day this past summer | Download this photo.

Studying tick risks and crafting solutions

At Kansas State University, researchers are continuing to study both the tick and the disease it carries to better understand how they interact with local environments and cattle systems.

Through KVDL and K-State Research and Extension, the university shares information with veterinarians, producers, and industry partners to prepare the state for potential future detections.

“What we’ve learned in the last two years is amazing,” Hanzlicek said. “Two years ago, we knew almost nothing about this parasite in U.S. herds. Now we’re beginning to understand its behavior and how producers can respond.”

That collaborative approach, Hanzlicek added, reflects K-State’s long-standing role in serving the people of Kansas through science, education, and shared problem-solving.

He encourages producers to stay informed but not alarmed.

“This detection tells us the tick is here,” he said. “It doesn’t tell us how widespread it is or how long it’s been here. By reporting what we see and working together, we can stay ahead of this challenge.”

###