Paging through the past

These are some of the oldest printed books in K-State Libraries' Morse Department of Archives and Special Collections

hen talking with classes or other groups about old books, we often use the word “incunables.” But what are incunables? In the rare books field, the earliest printed books in Europe — those from the 1450s through 1501 — are incunables, or the singular, incunable.

In 1455, Johannes Gutenberg completed the Bible that commonly bears his name. Although he is known to have started printing as early as 1439, his 42-line Bible is marked as the beginning of printing in Europe with mechanical movable type.

Gutenberg did not invent printing. Printing presses are known to have been in use in China since the 700s. Gutenberg's contribution to printing is mechanical movable type. His type design was mass produced, and the printing revolution quickly spread throughout Europe.

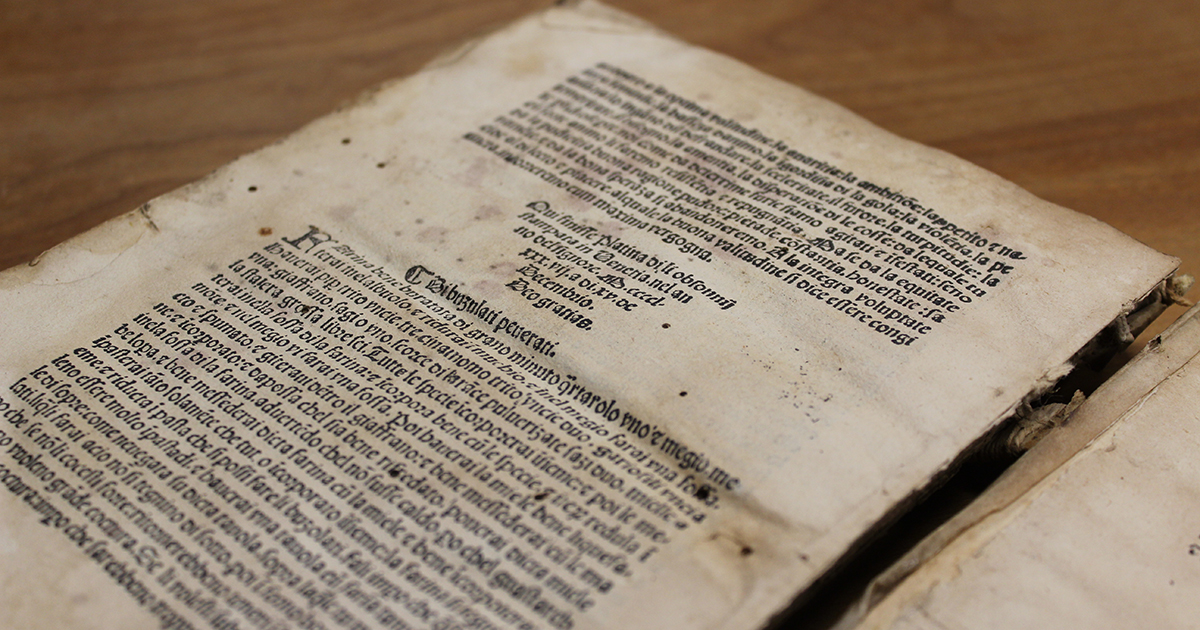

K-State Libraries' collection of complete incunables includes a translation of Bartolomeo Platina's “De honesta voluptate et valetudine” printed in 1487. Above, the Latin exclamation Deo gratias, means "thanks be to God."

The British Library's Incunabula Short Title Catalogue (ISTC) estimates that 51 titles were printed between 1452 and 1460 in Europe. In the last decade of the 1400s, 13,004 titles were printed. An estimated 28,000 titles are believed to have been printed in Europe by 1501.

Gutenberg's mechanical moving type truly did create a revolution in the dissemination of knowledge.

The Richard L. D. and Marjorie J. Morse Department of Archives and Special Collections at K-State Libraries has a small collection of four complete incunables, as well as many single pages from other incunables.

The finishing touch

One of the first things people notice about the incunables is that they do not have what we recognize as a title page.

Information about a book — the author, the printer, place of publication and date — was included on the last page of a book and is known as a “colophon.”

Unfortunately, many books have survived without any information about the printer or date of publication.

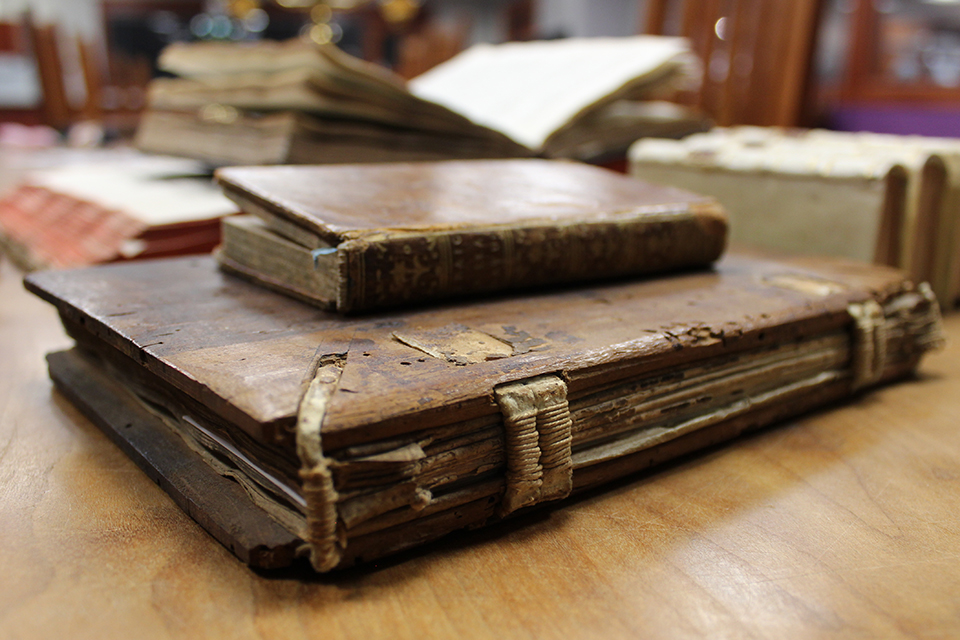

Various bindings from the 15th and 16th centuries. "De la honesta et valetudine" lost its leather cover a long time ago, now exposing the wood boards of its binding.

Although colophon is an 18th-century term meaning “finishing touch,” they were not exclusive to incunables. The earliest colophons date back over one thousand years, and in many manuscript books, scribes often wrote: “Finished, thank God.”

Early printing is also a transitional period from handwritten books. Many 15th-century books still included handwritten, illuminated initial letters or rubricated (red ink) initial letters, both of which may be elaborate or simple.

Vertical line rubrications often highlight important parts of a text or simply mark the beginning of a new sentence.

The oldest books at K-State Libraries

The oldest cookbook in the Libraries’ Cookery Collection is an incunable from 1487. Bartolomeo Platina's “De honesta voluptate et valetudine” (“On right pleasure and good health”) appeared in print around 1474 and soon became the first mass-produced cookbook.

The Libraries' copy is an Italian translation printed in Venice by Hieronymus de Sanctis, an accomplished wood carver, making it the first cookbook printed in a native language. It was the fourth book he completed in the first year he started printing.

"De la honesta voluptate et valetudine" was purchased by the Friends of the K-State Libraries in 2004 to mark their 25th anniversary.

Like scribes before him, the final line of the colophon reads: “Thank God.”

The three other incunables in Special Collections were printed in 1486, 1488 and 1498. The oldest is a brief letter from Pope Innocent VIII and was printed in Rome in 1486.

Our 1488 book is “Sermones Thesauri novi de sanctis” (“A treasury of sermons about the saints”) by Petrus de Palude and was printed in Strasbourg, Germany.

“Missale ordinis Sancti Benedicti” (“Missal of the Order of Saint Benedict”) was printed in Speyer, Germany, in 1498 by Peter Drach and is commonly referred to as the Drach Missal.

“Every one of these old books has so much character,” said Aly Youngers, a student assistant in the archives and special collections department. “If you sit with them long enough, you get to thinking about how somebody took the pains to print them. You'll also think about how someone long ago read this book and made notations in the margins for passages they wanted to remember.

“In a sort of sentimental way, it makes me want to remember too.”

Roger Adams is an associate professor and rare books librarian for K-State Libraries. This story originally appeared in the Winter 2024 edition of K-State Libraries Magazine.

###

Get K-State news in your inbox

Subscribe to receive K-State news directly to your inbox every Monday.