Source: John Leslie, 785-532-6176, jfl@k-state.edu

http://www.k-state.edu/media/mediaguide/bios/lesliebio.html

News release prepared by: Erinn Barcomb-Peterson, 785-532-6415, ebarcomb@k-state.edu

Monday, June 15, 2009

RESEARCHERS FROM AROUND THE GLOBE COMING TO K-STATE JUNE 21 FOR WORKSHOP ON A FUNGUS THAT CREATES PROBLEMS WORLDWIDE FOR THE FOOD SUPPLY, HUMAN HEALTH

MANHATTAN -- Fusarium has been responsible for eye infections from contact lenses, devastating losses of Australian cotton crops and threatening the commercial banana business in Central America.

Strains of this fungus pose a threat to the food supply, economies and -- more rarely but more dangerously -- human health.

On June 21, researchers representing nearly 30 countries are coming to Kansas State University to better understand Fusarium and strategies for dealing with the fungus. The Fusarium Laboratory Workshop, now in its 10th year, is a community effort, said John Leslie, head of K-State's department of plant pathology and one of the workshop leaders. A book produced for the workshop is used worldwide and is now in its third printing.

With colleagues, Leslie has identified and named four species of Fusarium, with several others on the way. He said that more than 1,000 researchers worldwide work on Fusarium, a common fungus found on plants, in soil and in the air worldwide.

With colleagues, Leslie has identified and named four species of Fusarium, with several others on the way. He said that more than 1,000 researchers worldwide work on Fusarium, a common fungus found on plants, in soil and in the air worldwide.

"The simplest rule is that if it is green, there is a Fusarium that will be able to attack it," he said.

Leslie said that the potency of the fungus lies in the diseases that it causes and because it produces mycotoxins, a couple of which are on the U.S. federal government's select agent list.

"Mycotoxin levels often are included in trade agreements on grain and farmers can get docked at the elevator if the contamination level is too high," he said.

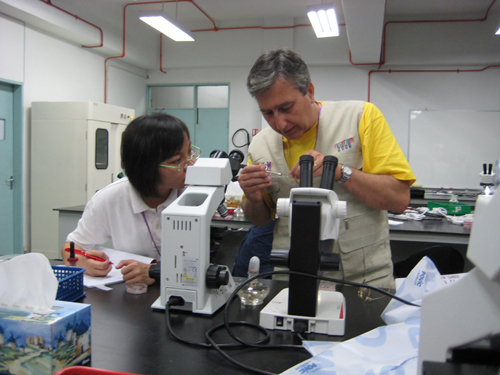

Leslie and colleagues initiated this incarnation of the workshop in large part to teach researchers and professionals how to identify a basic set of 25-30 species of the fungus. Traditionally, scientists relied on what they saw under the microscope, which can be somewhat subjective.

Leslie said that using DNA analysis to identify different strains has helped answer questions of more than 100 years standing while, at the same time, raising a whole new set of questions that scientists never dreamed to ask, let alone answer.

"Many problems arose because different species looked the same," Leslie said. "As you begin to tell those species apart with the DNA-based techniques, the breeding programs to look for resistance and the screening programs to look for toxin production become much more efficient because strategies are more focused."

The ability to screen for a particular species, or even a specific strain, of Fusarium offers more opportunities to deal with species-specific fungi, Leslie said.

"One of the big advances from our research is that the breeder can now can screen against the strains that they really care about," he said. "The first year that we figured out that the major pathogens on corn and milo were different we gave the milo strain to the K-State sorghum breeder. She came back and said, 'You flattened my whole field.' That's good, because the ones that were standing really meant something."

Such application, Leslie said, underscores the importance of the type of research he and other researchers do at K-State and that his colleagues are doing around the world.

"There's always the push for applied research, but we have to do the basic stuff to have some of those moments when you can say, 'Aha! We have a use for this.' The basic underpinnings are very important," Leslie said.

One project in his lab is currently funded by the International Sorghum, Millet and Other Grains Collaborative Research Support Program, known as INTSORMIL.

"We've been looking at a lot of strains from subsistence agriculture from Africa and, again, we're finding the same problem," he said. "There are all of these strains that look alike, but genetically they're different."

Identifying and understanding Fusarium is vital to various professions and disciplines, Leslie said. The workshop draws people from academia, industry, health care, agriculture and air quality control.

"The workshop is a huge unifying force for this whole field, and encourages people who are in very different fields to all communicate with one another about what they have in common and to educate the others about things that are different," he said.